The lack of representation is something that is returned to time and time again. Without representation we cannot accurately credit black women’s contribution to the art world. Whilst this barrier is in place, it will always be difficult to fully celebrate and praise their work. It will be a challenge to correctly document and archive their submissions into the artistic sphere.

Christabel Johanson on Black Women in the Arts

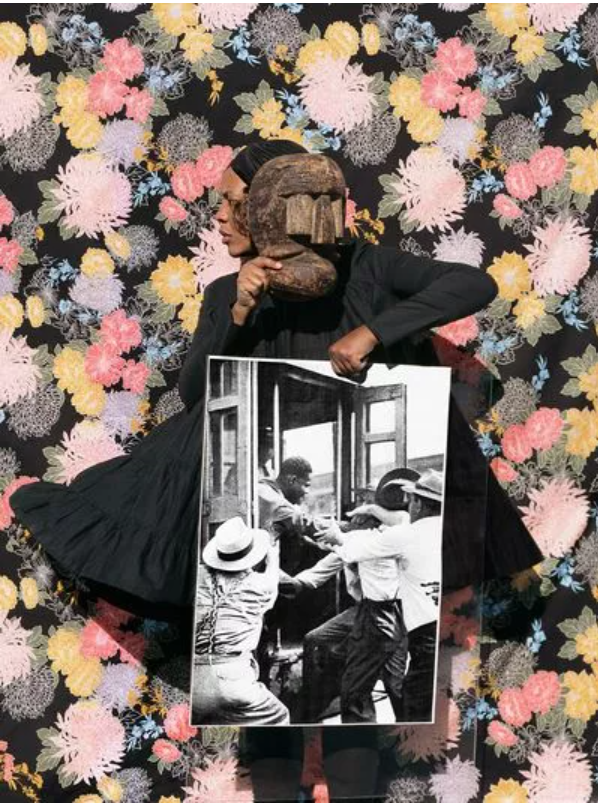

Simone Leigh, Facade, 2022, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery, New York

International Week of Black Women in the Arts

This February the United States celebrates the International Week of Black Women in the Arts. The event turns the spotlight on artists from various fields including cinema, music, painting as well providing a platform to support them. Issues of representation, equal pay and other areas of awareness are raised during the week.

It is an important event charting the history, progress and excellence this field provides. It also highlights the many ways society can further support black women. For instance, nationalday.com reports that women comprise of approximately 51% of visual artists. Yet make a mere 3-5% of permanent collections of exhibitions. This is just one example of the gulf between male and female artists and why weeks like these need to be observed. It leads to questions like, why are there more female artists yet so little representation in the top tiers of the art world?

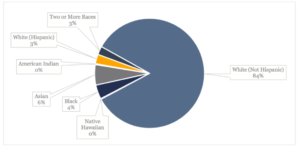

Female performers like actors and dancers, literary figures and other artistes are doubly discriminated against on grounds of their gender and race. It may not be a surprise to hear that black women face twice as much discrimination, but it isn’t until we hone into a microcosm like the art world that we see how pervasive it is. According to the National Museum of Women in the Arts, just 11% of acquisitions made by prominent museums in the US over the past decade were by females. Unsurprisingly the majority of collections come from white men, with all other groups such as Asian or Latino men or white women garnering less than 1% each.

Perhaps a steer in new directions may come from the executive boards and programming teams. After all they shape the future curations and focus of exhibitions. Yet if more diversity needs to be reflected externally in shows and curated work, then surely this must first be reflected in the diversity of its own staff and decision-makers?

Only 4% of museum employees in a curating or educational role are black, according to a 2015 survey (1). Then a paltry 24% of leads in museums are female – this includes the largest and wealthiest institutes with budgets of $15million or over (2).

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey (2015)

Some museums are leading the way, such as the National Museum of African Art or the Studio Museum in Harlem. These places have seen black female directors at the helm. We find that this example is mainly being led by institutes that already focus on the African diaspora. Thus, they are appointing opportunities in a more equitable way. Unfortunately, mainstream establishments like the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have only been led by males.

However, it isn’t all pessimistic, as taking stock of the past does allow us to celebrate the areas where black women have been given platforms to shine. Prominent artists, whom I have previously written about, like Simone Leigh and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye have made it to the ranks of leading galleries and even featured as headline names. They serve as both aspirational figures as well and trailblazers in an industry that statistically still has a glass ceiling. Yet by giving these artists a platform to showcase their work, galleries and museums open up their audience base. Previously categorised as a space for the wealthier, educated or white patrons, these spaces can grow to embrace a wider viewership.

In a Marie Claire interview Isolde Brielmaier, curator-at-large for the International Center for Photography (ICP) commented on the power of art to open up perspectives (3). “One of the things that art does is it can actually challenge you to think more deeply or differently about identity, how we see it, or what we actually think it is.” Discussing the contributions of black women, who have been creating for centuries, and the barriers that stand in their way Brielmaier says, “While it has a long way to go in terms of inclusivity and equity and parity, I would argue things have opened up a little bit. There’s a greater number of Black artists that are being shown at institutions.” Although this opinion can be subject to dispute, in the spirit of the occasion, there are definitely up-and-coming artists who are pushing at the fringes into the limelight.

Xaviera Simmons is a mixed media artist who Brielmaier describes as not adhering to “one particular style or sort of vision of her work. And that’s tremendous. You imagine that sense of freedom.” Simmons has worked with photography, sculpture, video and performance art. She has been shown in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA, New York), the Museum of Contemporary Art as well as Studio Museum in Harlem amongst others. Her work has been acquired by MoMA, the de la Cruz collection in Miami and the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. Therefore, Simmons is an example of a black female artist who is treading a rarer path than most of her peers. Simmons once said, “Whiteness must undo itself to make way for the truly radical turn in contemporary culture.”

Sundown (Number Twenty), 2019. (Image credit: Courtesy the artist and David Castillo)

Another artist is Delita Martin whose work presents the marginalised figure of the black woman in a codified way. Using symbolism and language as the expression of her art, Martin connects multiple generations of black women as well as multiple layers of interpretation. Martin similarly has been featured in museums, notably The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. “Martin’s current work deals with reconstructing the identity of Black women by piecing together the signs, symbols, and language found in what could be called everyday life from slavery through modern times. Martin’s goal is to create images as a visual language to tell the story of women that have often been marginalized, offering a different perspective of the lives of Black women.”

Star Children: I See God in Us series, 2019, Acrylic, Charcoal, Decorative Papers, Fabrics, Hand stitching, Liquid gold leaf. (Image credit: Courtesy of Delita Martin and Galerie Myrtis)

Martin’s biography states that “Throughout history, the marginalization of Black women has led to problematic representations of their roles within community and family structures, as well as problematic visual and textual representations; thus, making it difficult to document their positive contributions within collective systems.” The last line in particular strikes a chord with the ethos of International Week of Black Women in the Arts. The lack of representation is something that is returned to time and time again. Without representation we cannot accurately credit black women’s contribution to the art world. Whilst this barrier is in place, it will always be difficult to fully celebrate and praise their work. It will be a challenge to correctly document and archive their submissions into the artistic sphere.

International Week of Black Women in the Arts is not only an important social occasion but a politically-charged one. At its core, it is a celebration of the artistes that have paved the way through time for all black women to be recognised in the Arts. Considering the tradition of crafts and tribal art in Afro-Caribbean communities, especially matriarchal sects, it is almost taken for granted that the body of work to look at is endless. Whilst this is historically true, its record in museums and galleries proves to be relatively sparse. Therefore, through this occasion’s very existence, it highlights the disparity between black women and the status quo. When we celebrate where black women are in the industry, we also observe where they are not. This leads to necessary enquiries as to why, as well as when and how this will change. Its impact is derived from its absence as much as its presence – and that is something to be celebrated.