‘I want to do projects that uplift the communities I belong to by using positive imagery. I want to cherish Black and Brown beauty, celebrate our heritage in a way that fights a system that establishes one-way of life and tells what and how things and people must be.’

Afro-Mexican artist Irene Reece about The Family Album as a Source for Activism

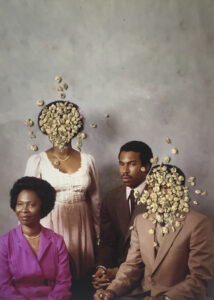

Strange Fruit 2, courtesy of the artist

Irene Reece: The Family Album as a Source for Activism

‘… if you are alive, you are descended from a people who refused to die. Nothing is more sacred than you.’

Arianna Brown, Curanderismo

Irene Reece is an Afro-Mexican American contemporary artist and visual activist based in Texas whose work combines vernacular photography mainly from her family album, art photography, text, film, and installation. Reece works in a number of projects at the same time and hardly ever considers them complete. By consciously leaving her projects open, the artist revisits them frequently and adds new layers of signification. This uninterrupted expansion serves as a metaphor that reflects the artist’s own growth as an individual. Her methodology is then a meditative circular continuum, driven by processes of re-thinking and expanding. Key to her practice is also the ecology of the circulation of images, instead of just creating new ones, and preserving family’s history; the artist often repurposes photographs that have been previously included in other series, adding further meaning to the images from her family album and robusticity to her narrative.

Kin, from the series Billie-James, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Irene’s work addresses a myriad of themes that range from mental and community health to family histories, social injustice, and arguably mainly, racial identity. In the words of the late Stuart Hall ‘identities are the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past’; Reece utilises her practice as a cathartic process that, on one hand enables her to get over the being ‘positioned by’, that is being the subject of Otherisation, and on the other, allows her the agency to balance her position within her different identities.

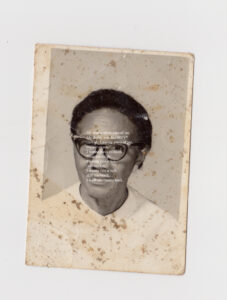

‘My identity is being questioned continuously. When I was in France studying my MA, I was identified as Mexican, whereas when in Houston, I’ve suffered discrimination within the Latinx community due to being half black.’ The series Birth Certificate plays homage to both her heritages. The work, which functions as an altar, is composed by a number of photographs that trace the artist’s family tree and also objects that reference the Afro-American and Mexican traditions and culture; for instance, white flowers are used in wake ceremonies and funerals, the artist adds them to the surface of the images of those family members who have passed away as a form of grieving.

Installation shot Birth Certificate, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

From the series Birth Certificate, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

In Limitation, the artist appears carrying a cotton bale in reference to the manual labour endured by her ancestors, at the same time that sports the “Milagros” (miracles) from the Mexican folklore, a protective charm carried by her ancestors for healing purposes that permits Reece to share a message of care and hope. However, the famous quote by James Baldwin that accompanies the image ‘I picked the cotton, and I carried it to the market, and I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing’ indicates that the reality of BIPOC people hasn’t changed, as racial divide and overt racism is still at stake today.

Limitation, from the series Billie-James, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

The Power of Text

Being brought up in a family of writers and books lovers, there is a prominent presence of text in Reece’s oeuvre: ‘sometimes words have a bigger impact than images, so I pair them together.’ She appropriates the work of writers she grew up with reading or that her father read to her, such as Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Stuart Hall, and Langston Hughes. The artist combines these texts with contemporary images of her own to stress the fact that things haven’t really changed, as if we live in a time of sorts where real societal advancement is only part of a politically orchestrated delusive agenda.

Freda Pie, from the series Dogs that Bark don’t Bite, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Not only does Reece appropriates quotes, she also interrogates the apparently innocent use of text and language to examine how these have ingrained the stereotypes about African American people and to uncover the hidden meanings and histories. In her series Dogs That Bark Don’t Bite the artist disassembles the African American folklore learnt by children from a very early age. Amongst others, she uses alphabet-shaped pasta with which children play, as a reference to the school days and how children from a very early age are influenced by racist narratives contained for instance in nursery rhymes that even the artist herself grew up singing such as Baa Baa Black Sheep or Eenie, Meenie, Miney, Mo.

Re-dressing conventions by way of positive imagery

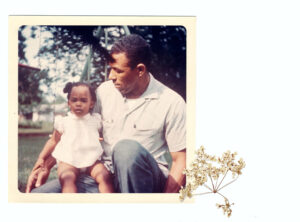

When selecting images from the album, the artist makes conscious choices: ‘I select images that are considered positive imagery so to dismantle the prevailing narrative around African Americans. For example, in the north American cosmology, black children are stripped off their childhood, as they are considered a threat from an early age, so I tend to use a lot of images with children that I find in the family album just so they can be seen in their purest form.’

Protect Black Girls, from the series Emblematic of Black Souls/Home-goings/front- and back, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

For Reece there is a discrepancy between the extended narratives and her experience growing up, and this is even more so when it comes to the figure of the father. The media has persistently portrayed black fathers as absent or abusive, yet recent research has shown the opposite. Having had nurturing and loving masculine references during her upbringing, the artist uses the tools available to her to disarm the media portrayal of black fatherhood.

That Generational Love, from the series Billie-James, 2019. Courtesy of the artist.

Irene Reece doesn’t think of her practice as ‘universal’. She refuses to produce artwork for everyone. She declines following homogenising parameters that would simplify her work to please larger audiences at the expense of eliminating different individual identities: ‘I want to do projects that uplift the communities I belong to by using positive imagery. I want to cherish Black and Brown beauty, celebrate our heritage in a way that fights a system that establishes one-way of life and tells what and how things and people must be.’