I write and make art from a black perspective because I think it’s needed and it makes me feel like I own my stories. I feel like it’s beautiful, it’s resistant and it’s powerful.

John Jennings in conversation with Christabel Johanson

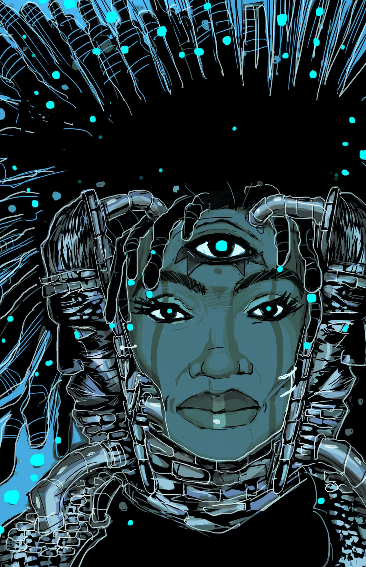

Mickanah. Black Kirby Series, 2015

John Jennings

John Jennings is an illustrator, editor, bestselling author and Professor of Cultural and Media Studies at the University of California at Riverside. Some of his accolades include the 2017 New York Times Bestseller title for Hardcover Graphic Books and in 2018 he won the Eisner Award for Best Adaptation for Kindred. In his work Jennings investigates visual representations of race in Film, Comics, Fiction and Graphic Novels with a particular interest in Black Culture.

How did you get involved in illustration and in particular in comic book illustration?

I’ve always been interested in art for as long as I can remember. I probably started drawing from when I was about four years old (according to my mother). My mother got me my first comics and I was hooked on them since then. I started trying to make comics around nine or ten. The images just always appealed to me. I honestly can’t remember a time when I wasn’t into comics, now that I really think about it.

(cover art) Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci Fi & Fantasy Culture by Ytasha L. Womack (2013)

So, I started working professionally as a comic artist in the independent space in about 2001. Since then I’ve made a space for myself as a comic book illustrator, cultural critic, and cultural activist related to representation of diverse images in comics and sequential art.

What is your artistic process when illustrating? Do you draw inspiration from the scenes and writing or another approach?

The process varies from story to story. I’m trained as a graphic designer so my brain is always attended to what the “problem” is. Each story is a potential solution to an issue or need put forth by the writer. Sometimes that person isn’t me and sometimes it is. So the images come from the meanings in the script but also from the potential allegories afforded by the narrative. I always start with the characters. The characters are the most important index for the story. They are the proxies for the reader and they must be well thought out and designed. They must be consistent or the story falls apart.

If I am adapting a story from another medium, then I like to print the story out and draw directly on the pages. I like to plan out the sequences and try and figure out pacing by making little notes on the story edges. Then I do thumbnails of the layouts. Then I do sketches to that eventually become full blown drawings. Once that is done, I ink the pages and then finally add colour.

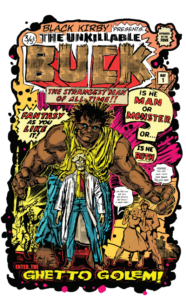

(cover art) The Unkillable Bulk. Created by Black Kirby (John Jennings and Stacey Robinson) and Tim Felder

Which illustrators do you admire and why?

I think my inspirations come from so many sources. I don’t distinguish between “high art” and “low art”. So my influences go from someone like Otto Dix to Frank Miller. I think in general I am attracted to bold line usage, strong and dynamic page layout, and abstract and immediate compositions. That is something that is consistent throughout my influences whether they are considered illustrators for fine artists. So, besides the aforementioned Otto Dix and Frank Miller, I also love the work of Egon Schiele, Ben Templesmith, Lois Maillou Jones, Denys Cowan, Ted McKeever, Palmer Hayden, Romare Bearden, Aaron Douglas, Dave Mckean, Neal Adams, Gil Ashby, Franz Masreel, Kathe’ Kollwitz, Lynd Ward…the list is so long. But I am also really influenced by filmmakers like Spike Lee, David Lynch, Gordon Parks, Ridley Scott, and John Carpenter.

In the foreword of The Blacker the Ink, the Black body is likened to an inkwell in which the “flexible, mutable, liminal nature of ink” is contained. In the earlier days this seemed more like a confined space where Black identity wasn’t allowed to be as expansive. When do you think this changed?

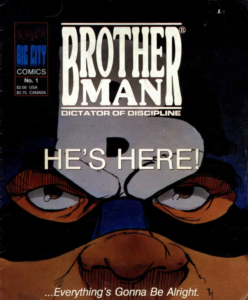

I think that the Black Body in comics starts to change when black people start having more control over the images. So a lot of that happens in the black cartoon strips that were from the black newspapers. The first black comic book was in 1947 but, even before then, you had cartoonists like Ollie Harrington and Jackie Ormes in the black press creating smart, black, well designed stories and characters. You don’t get the first black writer in mainstream comics until the 80s. That’s Christopher Priest. He helped usher in a new way to see blackness in superhero comics. The black indie press really jumps off in the 90s with titles like Brotherman, the books from Ania, and the Milestone Media books distributed by DC Comics. The Black Age of Comics, started by Turtel Onli in Chicago, is where you really start to see diversity though.

The Black Ink edited by Francis Gateward & John Jennings

Brother Man (1990), Dawud Anyabwile (artist) & Guy A. Sims (writer)

How does the physicality of Black superheroes relate to society’s perception of the Black body? Do you feel this works differently with White bodies?

Superhero comics are very much about power fantasies. Usually these power fantasies are read by cisgendered, heterosexual white men. Black bodies have traditionally been either hyper-sexualized or seen as hyper-masculine, so those bodies tend to be seen as even more hyperbolic. When you look at the earliest black superheroes in mainstream American comics, they are very much centred on the performance of a particular type of blackness. They were very influenced by Blaxploitation films so that comes out in the visual vernacular and in the way they were written. Also, the amount of skin that was shown was over the top. A great deal of those characters have been reconciled but they started out really leaning into what white writers thought black people sounded like and acted like.

Which Black comic book character is your favourite and why?

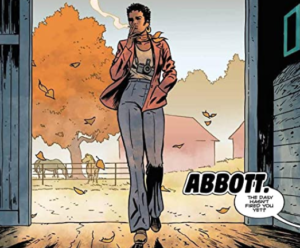

That is super tough. I am torn between this journalist character called Abbott and this police detective called Theodore Dumas who is the main protagonist in this supernatural crime story called The Black Monday Murders. Abbott is set in the early 1970s and she’s like…if you took Karl Kolchak from the 1970s TV show the Night Stalker and fused her with like Foxy Brown or Friday Foster. The story is based in Detroit and she’s a tough as nails, sexy, stylish journalist who stumbles upon a supernaturally oriented missing person’s case. Dumas is the lead detective on a case of murder that is involved with magic and the stock market. Both characters are “seeker’ characters who are hacking into white spaces and they’re using their intellect to do so. I think I’m going to go with Abbott but Dumas is a close close second.

Abbott by Saladin Ahmed. Sami Kivelä (Illustrator), Jason Wordie (Colorist)

Earlier comic book movies e.g. Spawn, Blade, or even Halle Berry’s Catwoman portrayed the figure of an anti-hero. Now examples like the Black Panther feature a clearer protagonist. Do you feel this is a politicised update?

All art is political. I think that what’s happened is that the interest in Afrofuturism and Black Speculative culture has boosted the level of detail and interest in Black Superheroes. In addition to those you mentioned, you also had films like Blank Man and Meteor Man that were comedic in nature. I think today’s superheroes of colour have moved past most of the stereotypes connected to mediations of blackness. The demand is for more complex characters and the producers of these stories are finally paying attention.

What sort of Black narratives do you wish to see explored more, or explored in a fresher way?

I think that images of protest will always be needed in regards to the black subject. I also think that images that relate to some of the more horrific aspects of our history will have to persist, lest we forget. However I have become increasingly interested in images that are filled with a radical love of black life and a serious investment in black joy. We have to remember why we fight. We use our stories to fight for love.

I think there is something in empowering Black content-creators to tell their stories rather than “through the lens” of Blackness. How does society balance promoting Black platforms without commodifying Blackness?

I think that as long as we are under a capitalist system that commodifying cultural representations will always be a thing. I think that there needs to be more ownership of black spaces to make sure the expressions are empowering and true. I am very Morrisonic about the things I make and things I write. I write and make art from a black perspective because I think it’s needed and it makes me feel like I own my stories. I feel like it’s beautiful, it’s resistant and it’s powerful. Also it normalizes a black perspective and puts people who aren’t black in a space where they can extend empathy and understand a different perspective. I think that black folks have always had to do that with white protagonists. It’s time our stories and images were met with the sane compassion and interest.

What advice would you give to young Black artists and writers hoping to emerge in this industry?

Don’t try to be like anyone else. Understand that have to work very hard to find your voice. Never give up on getting better. Read both deeply and widely. The best comic creators don’t read just comics.