“If we could combine the autonomy and respect for local talents of the Kampala Biennial with the website and communicative power of KLA ART 14, an ideal contemporary African art festival could be created in the future in Kampala. African contemporary artists are quite able to organise themselves and speak for themselves, provided they can secure enough funding to cover transport, logistics, materials and expenses. The ‘help’ of expatriates should be more or less invisible, and this was not the case at KLA ART 14.”

Helen Hintjens reports from the Kampala Art Festival.

KLA ART 14

The Kampala Art Festival has a voice to explain ideas.

Building on the success of the festival in 2012, KLA ART 014 offers a platform to showcase new and emerging ideas by contemporary Ugandan artists. KLA ART is a two-year process of thought, production and experimentation resulting in a unique festival, which directly links artists, artworks and audiences”

Rocca Gutteridge, Project Director, KLA ART 014

African Contemporary Art Rising

A growing number of contemporary artists from the African continent and diaspora appear to be rising stars in today’s globalised art market galaxy. At the 55th Venice Biennale, the Golden Lion award went to the Angola national Pavilion, and to Luanda-based photographer, Edson Chagas. (1)

One driver of this whole process is the extraordinary Okwui Enwezor, and what his example should suggest about how we curate international exhibitions like KLA ART. Enwezor was recently appointed curator of the next Venice Biennial, and has already curated the Documenta 2002 in Kassel, being only the second person to do both these jobs in a single lifetime. What has marked out this man from the start are his strides in de-ghettoising contemporary art from the African continent and the African diaspora, and recognising its close affinities with globalised contemporary art in general. As one website comments of him: “Enwezor’s curatorial project has been global since the beginning, pushing African and diaspora artists to the foreground”, within a broader and intense engagement with that is most challenging and global in contemporary art. (2). Enwezor’s faith in the “emotional and the poetic intelligence” of art is inspiring and appealing, meeting some hunger in Western art audiences, and perhaps also in the increasingly globalised art world centred more and more on Chinese markets.

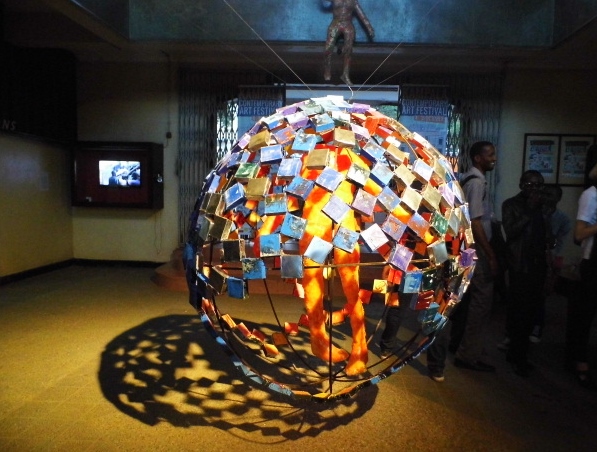

Derrick Komakesh, installation, 2014.

Derrick Komakesh, installation, 2014.

In the African continent, the number of art biennials is also growing. (3)

Starting with Dak’Art in Senegal’s capital in the mid-1980s, there were two notable Biennials in Johannesburg in the mid-1990s. More recently, Doual’Art was launched in Cameroon.(4) In August 2014, the first ever Kampala Biennial, themed ‘Progressive Africa’, took place, bringing together artwork from across the continent and beyond, with South African and Zimbabwean artists predominating. The selection was outward-looking, with artists like Ezra Wube from Ethiopia/USA, Florine Demosthene from Ghana/Haiti and Gillian Gibbons from Uganda and UK. (5) Yet importantly, the Kampala Biennial was home-grown, and was deliberately: “…organized by Ugandan artists, with support from local institutions, to reach a local audience. The curatorial team and jury at the Biennial consist of African artists, art managers, and critics”. (6) The emphasis was thus on a locally grounded art festival.

Yet unlike the Kampala Biennial, KLA ART 14 is tremendously well documented, with film, artists’ profiles and details of a range of activities on an excellent website. In this piece, I question whether the emotional and poetic intelligence of the African contemporary artists represented in KLA ART 14 needs to be expressed by a Western director. Why can’t KLA ART 14 be fully organised by local artists, as was the Biennial?

Awakening the Railway Station

In late September 2014 I was in Kampala for work, and heard through facebook from a contemporary artist I greatly admire, Vitshois Mwilambwe Bondo, that he had travelled from Kinshasa to Kampala to take part in the second KLA ART Festival. Would I come to the opening? So, on the first day of October, I walked through Kampala traffic jams to find the old railway station, and found a strange sense of peace and life inside. Although the building was closed since trains ground to a halt in 1998, this venue generated a sense of movement and of optimism, as if building on the colonial wreckage of the past to create something fresh. Till the end of October, works of contemporary artists from Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Kenya were on display inside and around the Railway Station building. A boda boda (motorbike) project involving 20 budding Ugandan artists would be staging events round the city, and there were special visits to artists’ studios in and around Kampala, every Wednesday at 10 a.m. Everything was free. How was KLA ART 14 possible, so shortly after the first Kampala Biennial?

Mulugeta Gebrekidan, The Creativity of Survival, 2014.

Mulugeta Gebrekidan, The Creativity of Survival, 2014.

A relic of wrought iron and stern notices, the station is transformed through the vibrant collection it now houses, temporarily, of sophisticated and challenging contemporary art from across the East African region. It is in fact a curators’ dream come true for the co-curators of KLA ART 14, Moses Serubini, Violet Nantume, Robinah Nansubuga, Hasija Mukyala and Philip Bahimunsi. This talented and multi-faceted team, working with a meagre budget provided by the organization funding KLA ART 14, a really fantastic job of ensuring that a cross-section of artists could show their work in style. From veteran sculptor and painter Francis Nnaggenda, whose work is priced at international levels, to Paul Bukenya Katamira, an artisan artist whose barkcloth (not backcloth as the website calls it) forms the starting point for a fantastic installation, conceived between Karamira and Vitshois Mwilambwe Bondo, the man whose work I had come to KLA ART 14 to see in the first place. Bark cloth is beautiful and hangings and a book both explain in Luganda how the cloth is made.

Paul Bukenya Katamira, Ekkomagiro (installation with Vishois Mwilambwe Bodo).

Paul Bukenya Katamira, Ekkomagiro (installation with Vishois Mwilambwe Bodo).

My next treat was at the entrance of the building where, lit up at night in spectacular fashion, was the work of Paul Ndunguru, contemporary artist based in Tanzania and someone who uses every known to humanity, from film and music to sculpture, illustration and social media, in his work. Similarly accomplished, Helen Zeru is a visual artist based in Addis Ababa, whose film and stills were also to be seen in old display cases in the railway station main hall. Like many of the other invited international artists, both have exhibited internationally.

Paul Ndunguru, My Building Blocks, 2014.

Paul Ndunguru, My Building Blocks, 2014.

Helen Zeru, Inside out: One Foot In, One Foot Out, 2014 (Ethiopia)

Helen Zeru, Inside out: One Foot In, One Foot Out, 2014 (Ethiopia)

Another artist, from Rwanda, Tony Cyizanye makes enormous paintings, which he calls a map “I represent many people, a crowd of people, representing Ugandan people who have a voice to explain ideas or what. So I make an abstract to represent many things”.(8) The painting is about 4 meters long and at least 1.50 meters high.

Tony Cyizanya, We The People, 2014 (detail).

Tony Cyizanya, We The People, 2014 (detail).

One well-embedded Ugandan artist, Hellen Nabukenya and her partner, run ArtPunch studio and exhibition space, where Ugandan artists can work and hold shows. (9) I asked her if they made a living from art, and she laughed and said that yes, art was their daily business. Hellen’s hanging was the first thing you saw at the front of the old Railway Station. Entitled ‘Golden Heart’, this huge woven work, made of pieces of fabric, expresses for her the kindness of women as they work together, making ‘something nice’ from next to nothing.

Hellen Nabukenya, Golden Heart, 2014.

Hellen Nabukenya, Golden Heart, 2014.

Next I enjoyed the spectacle of the boda bodas, or motorcycles, collected for the opening on the old station platform. To my mind, Babiyre Leila Burns’ work, designed to protect boda boda drivers from accidents, and made entirely of blue, green and transparent plastic bottles, combined beauty with a political statement about safety. The hospitals are full of those who fall off boda bodas, trying to get home or to work. Another artist, Grace Sarah uses the boda boda for a more prosaic message, reminding us that these motorbikes are also used to transport animals in rural areas. Ken Misoke’s simple multi-mirrored motorbike conveys how the boda boda phenomenon elicits a lot of differing opinions in Uganda. There is even talk of banning them. (10)

Boda Boda, KAlule KAgga, 2014.

Boda Boda, KAlule KAgga, 2014.

Looking for Vitshois Mwilambwe Bondo

All of this was most enjoyable. Still, I was not satisfied as I had come here to see the work of Vitshois Mwilambwe Bondo, an artist whose work I had admired for several years, and never seen except through photographs. However his work was nowhere to be seen at the opening. Instead, I was shown a dark space with some shapes inside it, not yet displayed, incomplete. I wondered why this was, and asked him. How come he had collaborated with another artist, Paul Bukenya Katamira, but had neglected his own installation which was also part of the show? No, he assured me, the problem was not that he had neglected his own work, but that he had not been given a suitable space for showing it. Vitshois had been allocated a damp, broken room within the old station building; a space he had insisted with the Project Director was not suitable. She did not think there was a problem, and eventually in order to be able to show his work to its best advantage, he was forced to find another, more suitable location for himself, with the help of a couple of the curators. Vitshois had spent the most part of a week replastering and mending the new space, which was also far from perfect, preparing it for his installation and projection. He had not yet completed the work, and as a result his work was not shown at the opening, a major disappointment for him, and for me. The pleasure I had so keenly anticipated, of finally seeing the work I had studied for a year, with my own eyes.

A couple of weeks later, some powerful images came through from Violet, the curator who has taken a special interest in Vitshois’ work, and a curator who shows real promise. Vitshois talks about his work in an official video on the KLA ART 14 website. (11) He explains how he gets inspiration from the ‘reality of how people fight day by day, struggling in their daily lives. His installation expresses that: “…it is very difficult for these people to be connecting to the dream”, and shows a person floating and being under water, sometimes with text floating around him, and projected against fragments of painted wood, a kind of projection on a collaged installation, the whole conveying a sense of fragmentation and the fear of drowning. Vitshois explores “the confrontation between reality and the dream”, a dream of wholeness perhaps and a harsh reality of making do with bits and pieces of this and that.

Vitshois Mwilambwe, Bondo Images, Day by Day, let me dream my future (installation), 2014.

Vitshois Mwilambwe, Bondo Images, Day by Day, let me dream my future (installation), 2014.

Curators and Funders

If we could combine the autonomy and respect for local talents of the Kampala Biennial with the website and communicative power of KLA ART 14, an ideal contemporary African art festival could be created in future in Kampala. African contemporary artists are quite able to organise themselves and speak for themselves, provided they can secure enough funding to cover transport, logistics, materials and expenses. The ‘help’ of expatriates should be more or less invisible, and this was not the case at KLA ART 14. In 2011, Rocca Gutteridge and Nicola Elphinstone created 32o east, the Uganda Arts Trust, which has supported two KLA ART events, in 2012 and in 2014, further encouraging a thriving contemporary arts scene in Uganda and Eastern Africa.(12) This fantastic initiative shows that contemporary artists in the continent who obtain proper financial support can work together to make the kind of international quality art shown at KLA ART 14. Like contemporary artists everywhere, artists involved in KLA ART 14 needed only decent facilities and reasonable funding without strings to create. Since they live in the exhibition spaces most of the day, they should have sufficient budget to cover their expenses and should receive reasonable per diems.

KLA ART 14 benefited from high quality curating, and this was wisely left to Ugandans to manage. The whole set-up was fantastic, the location also. What slightly grated were just one or two well-meaning funders, who appeared to feel they deserved more credit than they received. Perhaps one lesson for KLA ART 16 is the delicate balance between the roles of artists, curators and funders. Curators need to be able to curate without worrying about their budget; artists need be able to make work in a space they feel good in; funders need to cough up and then remain mostly silent. Nothing however detracts from the fact this was a wonderfully well-organised contemporary art festival, with fantastic communication through the website, and strong elements of genuine public participation in almost every element of KLA ART 14. The organisers, artists and curators all deserve congratulations, and the funders deserve our gratitude for making it possible for all those involved to share this dream, at least.

#KLAART

www.klaart.org

http://klaart.org/bodaboda.html

http://klaart.org/studios.html

https://www.facebook.com/KLAART

https://hivos.org/news/kla-art-014-festival-representing-and-celebrating-unseen-urban-dweller

Footnotes

(1) http://africaunchained.blogspot.nl/2013/07/potent-art-spaces.html

(2) http://online.wsj.com/articles/how-okwui-enwezor-changed-the-art-world-1410187570 (Zeke Turner “How Okwui Enwezor Changed the Art World’, 8 September 2014, The Wall Street Journal)

(3) http://aadatart.com/the-emergence-of-biennials-in-africa/

(4) http://www.doualart.org/.

(5) ) http://kampalabiennale.org/selected-finalists/

(6) http://allafrica.com/stories/201408182873.html

(7) (http://klaart.org/exhibition2.html#

(8) http://vimeo.com/108755047

(9) https://www.facebook.com/ArtPunchStudio

(10) http://klaart.org/bodaboda2.html#

(11) https://vimeo.com/108781502

(12) http://www.roccagutteridge.co.uk/ugandan-arts-trust