Rob Perrée stayed for one month in Paris to experience Paris after the terror attacks of last year, but most of all to meet with contemporary African artists, to visit their studios or shows. Here a report of his trip.

Ernest Dükü, Miss Amuin @ soleil ô soleil, 2014

LET’S MEET IN PARIS

Contemporary African artists in Paris

Is Paris still Paris after the terrorist’s attacks of last year?

The statistics tell me that there are fewer tourists. The number of visitors to the Louvre for instance has fallen 20%. There are more police on the street and there are more soldiers around the city in general. Sometimes big streets are suddenly closed off. The so called escape streets, those that run down along the Seine, are blocked with planters. Being here for a month I could not figure out if there is a system behind these measures, but the absence of a system could easily be the system. I feel no threat; the possibility of another attack never pops up in my mind. Despite how traumatic the events of last year must have been, the terraces are filled again with Parisians having a good time, enjoying a drink, good food and each others company. In the area where I stayed – the Marais – nightlife is as intense as ever. To formulate it bluntly: everything seems to be back to ‘business as usual’. Of course, this is a view from outside and from an outsider. I can’t look behind doors, but I have talked to many people and the attacks are a rare subject of their conversation.

The issue of the refugees is far more visible. Never before have I seen so many people hanging around on the streets. Aimlessly, begging for money or sleeping. In certain areas of the city hundreds of people are living in tents, on the green strips in the middle of a boulevard. Near the Stalingrad subway station for instance. Sometimes the police ‘cleans’ these boulevards. A senseless, absurdist act. The day after……. the tents are back again. Where can they go? They make the failure of European policy painfully obvious.

1.

The first African artwork I saw in Paris was Dineo Seshee Bopape’s installation in the Palais de Tokyo: ‘Untitled (of occult instability [feelings])’. The context was a large red room in the basement of the building. The association with a bomb shelter was forced on me. Nina Simone’s song ‘Feelings’, played on a video screen, determined my second impression. On a video on the other side of the room power and what to do if you have the power were the topics. In between a big destroyed wall, suggesting a (war related?) disaster, and two video screens with beautiful, seducing images of a Parisian park. As always with Bopape: she puts all kinds of personal and political, often contrasting elements in a room – in a ‘messy’ way – and asks the viewer to make a story out of it. She uses emotions and emotional images as a trigger. The installation impressed me and at the same time, the work confused me.

Six years ago she was interviewed for Kunstbeeld Magazine. She said: “Art is one way of telling a story about society in a certain time. It is also a way of reflecting on yourself. An African saying states that one can only get to know a person through other persons. This mirroring is also art’s function.” She still could have said it in Paris, a few months ago.

2.

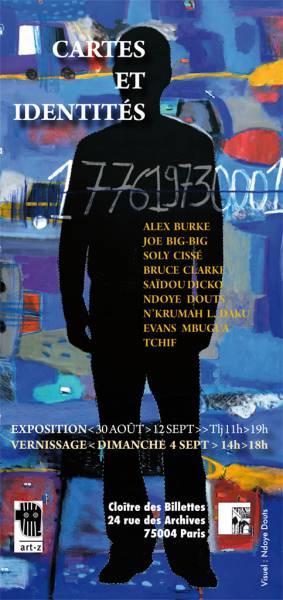

In a medieval cloister in The Marais, Cloitre des Billettes, was the group show ‘cartes et identités’ presented. Ten artists were showing work in the inner court of the cloister. A beautiful space, rough, visibly old, authentic. A dream space for an artist who likes to make large installations. However, the exhibition was disappointing. It gave the impression that it was put together at the last minute. It was poorly installed; the spatial possibilities and the character of the space were not used at all. From most artists – Nu Barreto, Soly Cissé, Bruce Clarke, Ndoye Douts and Tchif – I know much better works than the ones that were exhibited. That I could meet and exchange phone numbers with several artists made my visit worth the effort. And of course the cloister itself. One of these rare old buildings in the middle of the city.

3.

From the series: Les Maitres du Couteau. Couvent Etron Lahaori Kunde, Village d’Akoumapé, Togo 2011.

Last year I co-curated a large exhibition in Moengo, Suriname. Among the participating artists were Dany Lariche and Jean Michel Fickinger from Paris. They made beautiful, almost sculptural photographic portraits in Benin, Togo and Mali of the people involved in the rituals of the traditional culture. Not only to respect and honor the culture, but also to preserve the culture which is in danger of disappearing. In two books, till now, they have preserved their own work: ‘Divinités Noires’ and ‘Chasseurs de l’invisible’.

We met in Paris again, had lunch, a good time, and talked about their next trip to Mali to present their work there and to make new work. That series will be shown in Paris next year. More reason to come back is not necessary.

4.

From the series Faces, 2012.

Child of an African father – from Benin – and a Ukrainian mother, Dimitri Fagbohoun needed some time to decide that art was his real passion. He had all kind of professions before. As an artist he started with photography. He made interesting triptychs, but these works were not challenging enough for him. Now his main mediums are ceramics, video and installations. A lot of his work is about identity: born in Benin, living in Paris, mixed parents, a troubled relationship with his father who passed away without telling him that he was sick and struggling with his own position as a (divorced) father. Skeletons (death of his father); crowns, the bible, crosses, a confessional (referring to spirituality); white and black masques (symbols of hiding or of the connection between life and death) and references to traditional African rituals like nails in sculptures are symbolising the complexity of his theme. Poetic, vulnerable, emotional, personal are qualifications that fit his work.

Beside his work as an artist he is great in bringing people together. Because of him playing the go-between I could meet several other artists. Although Paris is a big city with a large African community – France had once many colonies in Africa – I got the feeling that most of the African artists know each other. They see each other at events; they organize meetings with each other etcetera.

5.

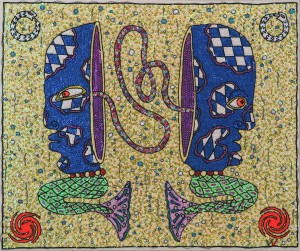

Mermaid, 2015.

For long it was law in France that every big housing project facilitated a number of affordable studios for artists. William Adjété Wilson lives and works in one of these studios. An enviable space.

He was born in France. His mother was French; his father was from Guin-Mina, on the coast of Togo-Benin. When he found out about his African roots – his father had changed his last name into Wilson when he moved to France – he decided to make them visible in his name. He added the African middle name.

He is a self-taught artist. Refreshing about being self-taught is that one does not care about the difference between high art and low art. He uses the medium he wants or likes to use, and he changes his medium if something triggers him in another medium or in another culture. Pastels, paintings, sculptures and assemblages, drawings and collages (with pieces of textile), textiles, photographs and videos, prints and illustrations, everything is possible. He wants to tell stories. Sometimes they are entertaining, sometimes they are about more heavy subjects (stories of migration). Sometimes for children (illustrated books for instance), sometimes for everybody who likes stories. He uses a figurative, elementary, personal and highly recognisable style. In some projects you can ‘read’ the source of inspiration: for his latest flag project (textiles) a visit to Haiti was influential.

For more than 35 years he manages to make a living with his art. He published many books and was in shows all over the world. He is not the kind of person who wants to impress with these achievements. He just does what he likes to do.

6.

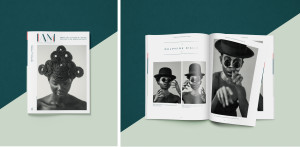

The Senegal Issue, 2016.

“IAM Magazine is the first artistic platform that celebrates women in the fields of visual arts, fashion, design and architecture in Africa, as well as the first artistic space focusing on women as an artistic subject. IAM Magazine is built on interactions; on people from different cultural, social and educational backgrounds coming together in one place to create intellectual bridges and further connections; and on a richness of exchanges and collaborations that stimulate opportunities for personal reflection, critical thinking and development. We pride ourselves on being a source of transmission among, and across, generations and continents in our goal to discover and explore the profusion of African contemporary creativity and to make the extraordinary achievements of women and artists visible and accessible at all time.”

This text I took from the website of IAM Intense Art Magazine. The magazine started in 2015. It organized a presentation in Paris while I was there. The founders invited young female artists, curators and art critics to talk about contemporary African art, with a focus on the roll of women. The room in Musée Quai Branly was ‘sold out’. An indication of the growing popularity of contemporary African art in France or a well organized and well published event? A combination of both factors, I think. The problem with round tables is always the same. The guest speakers are very eager to tell their story and at the end there is no time for questions anymore. This evening was no exception to the rule. For me the choice of the location was remarkable. The Musée Quai Branly Jacques Chirac (that is the full name, no kidding) is a post-colonial museum that shows art and artefacts from mainly former French colonies. Beautiful objects, no doubt about it, but often with a dubious history. How did they get there? What do they symbolize? What and who do they represent? Is the museum build to let Jacques Chirac look good or to show respect for Africa’s rich culture?

IAM is a beautiful magazine that does a good job. It deserves a better location to present itself.

7.

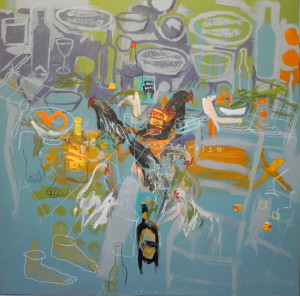

Diner avec volailles, no.3, 2016.

Strong Abstract Expressionist paintings with some footnotes of consumer reality in it. De Kooning mixed with Pop Art elements. The pleasure of making them shows. Gopal Dagnogo needs the right mood to work in his studio. If not, than he prefers to read a good book or not to work at all. He is not a career driven artist on his way to the top. He loves to make art, it would be great if he could make enough money with it to live on it, but there are more things in life that are important. His sense of humour goes with this attitude.

Gopal Dagnogo is born in Ivory Coast. He studied ‘les arts plastiques’ in Bordeaux in 1991, returned temporary to his country and moved to Paris in 2001. I know him a few years now. I wrote about his work on Africanah.org (https://africanah.org/gopal-dagnogo/). It is always inspiring to meet with him. When he invites you he tells you to “come with empty hands”. He is the host, he treats.

8.

The Hell of Copper, 2008 (Ghana)

“We have to meet soon because at the end of the week I go to Burkina Faso to work on my hotel.” Nyaba Leon Ouedraogo says it without blinking his eyes not realising that his reason to have me soon is not an ordinary one. Most Diaspora artists go back to their country to visit family, to work there for a longer period of time with talented students or young artists (Meschac Gaba, Barthélémy Toguo and others) or to buy property in case they decide to go back later in life, but to invest in a hotel is a variation I hadn’t heard before. Don’t get me wrong, Nyaba is not a capitalistic guy. Not at all, but he is not afraid of big changes in life. He came to Europe as an Olympic sportsman in track and field. The 400 meter was his speciality. Because of injuries his sports career came to an end. At first he did not know what to do next. By accident he met a photographer, he got fascinated by the medium, he asked him to teach him the technical things you need to know as a good photographer and, after a year, he started to make photographs. He is known now and his work is presented internationally. His ‘The Phantoms of Congo River’, inspired by ‘Heart of Darkness’ by Joseph Conrad, is an amazing series about the myths, the mystery and the harsh reality of that river. In another series he shows how the Western world dumps its electronic waste in Ghana. Poor people dig into it looking for copper wire because they can make a few dollars out of it. They don’t realize, and the West does not seem to care, that electronic waste can have a damaging effect on your health. Ouedraogo is a committed photographer with an eye for emotive details. Because his English is almost as poor as my French we had a sometimes puzzling, confusing and comic conversation, but, happily, his work does not need a lot of words to impress.

9.

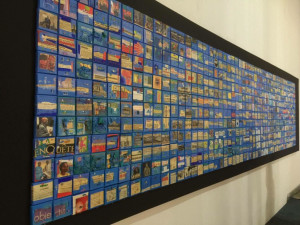

Kaleta 3 (Cherud), 2016

I met Emo de Medeiros at the Backslash Gallery. His ‘Transmutations’ show was running there. The show is one big narrative with an open end, a story in which tradition meets the twenty first century, in which different media are complementing or opposing each other, conceptual art meets figurative art, of which the amount of information elements on walls and floor can make you dizzy and confused. An installation as a fascinating, visual rollercoaster, open for multiple interpretations.

After a few minutes talking with him I understand why De Medeiros makes ‘busy’ art like that. He talks as if he is in a hurry. Driven, enthusiastic, full of ideas, juggling with references and names.

The greater part of the year he works in his studio in Benin. He is in Europe because his work is getting more and more attention. A recent review in Le Monde seems to underline that. When this article goes online, he will have an exhibition in London.

10.

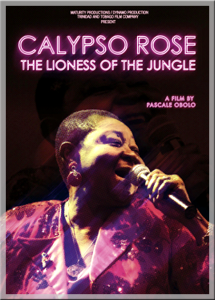

Angel in A @ Afrodisiaquement vôtre, 2013.

I meet Ernest Dükü (pronounced: Dookoo) in his house. His studio is in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, his home country. The house is ‘covered’ with his work. There is hardly any space left to move, let alone to work. But we manage to un-roll and un-folder his beautiful works on paper. A title is the beginning of his work process. From there he starts to ‘draw’. The word ‘draw’ is not really accurate, because it is more like painting and pasting pieces of text or image on paper. During the process he screws up (or do you call it wading) the paper he is working on and proceeds again. That wrinkling effect gives the works an interesting kind of vulnerability. Every work is a story full of symbols (and numbers) related to spirituality, to traditional African and, for instance, Egyptian culture, to traditions of writing, to ideograms, graphic systems and signs. Perhaps ‘pictorial writing’ says it more clearly. Sometimes the works are colorful (red can be dominant), in other works he limits himself to just a few colors. Although the content can be heavy, he always presents his ‘message’ in a light, playful way. The wrinkled paper fits with that concept. The dimensions of his works differ: from a hand-size picture to a work of more than 2 meters high and 1 meter wide. I can imagine how it will look and impress as you hang these works in an open space like the one in the Cloitre des Billettes in the Marais……………

11.

“What a boring meeting. Only older white men, no women, no young people, no people of color. How can you talk about the future of this museum without them? They are only praising each other.” Pascale Obolo is agitated when I – an older white man….. – meet her in the break of a conference in Musée Quai Branly. Obolo is a documentary maker from Cameroon living and working in Paris. She is the founder of the magazine Afrikadaa. With a group of people she is working on a platform for conversation and information about contemporary African art. It has to be realised in Paris and has to stimulate publishing too. “A conference like ‘Black Portraiture’ (1) is not very useful if there is no publication at the end. Publications are necessary to feed the dialogue.” During the last Dak’Art they made a start of their ambitious plans, next year in March there will be a follow-up-meeting in Paris. She has an urgent advice for Africanah.org: “stay in touch with your base, have an open eye for what is going on in Holland. The ‘Black Portraiture’ conference in Florence las year did not pay attention to the refugee problem in Italy at all. That is ridiculous.” About the success of African art: “It is mainly a commercial success. Galleries and auction houses are stimulating commercialized art. That’s not the same as good art.”

In November – 11 until 13- I will be back in Paris to visit the AKAA, the contemporary African Art Fair, one of the many fairs dedicated to African art. In the next edition of Africanah.org we will start the dialogue on the effect of art fairs – like African Art Fair and AKAA in Paris and the 1: 54 in London and Brooklyn – on contemporary African art.

-

‘Black Portraiture’ BLACK PORTRAITURE[S] III: Reinventions: Strains of Histories and Culturesis the seventh conference in a series of conversations about imaging the black body. It offers a forum that gives artists, activists, and scholars from around the world an opportunity to share ideas from historical topics to current research on the 40th anniversary of Soweto. Presenters will engage a range of topics such as Biennales, the Africa Perspective in the Armory Show, the global art market, politics, tourism, sites of memory, Afrofuturism, fashion, dance, music, film, art, and photography.The conference will be held November 17-19, 2016 at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) and held in collaboration with the U. S. Department of State, U.S. Ambassador to South Africa, Patrick H. Gaspard, Goodman Gallery, Hutchins Center for African & African American Research/Harvard University, New York University’s LaPietra Dialogues, Tisch School of the Arts and the Institute for African American Affairs.