While the fair 1-54 gave a stage to contemporary African art, works by other black artists were on display in several other locations in London.

Robbert Roos reports from The London Art Week

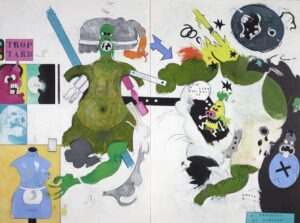

Hervé Télémaque Portrait de Famille, 1962-63 Oil on canvas 195.3 x 260.3 cm Photograph: Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève / André Morin © Hervé Télémaque, ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2021

FRIEZE, 1-54 AND OTHER HUBS FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN ART

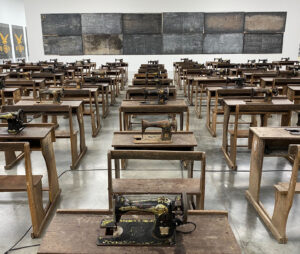

When 1-54 started in 2013, there was a lot of necessity to start an art fair focusing on art of African origins. The continent was underrepresented in most fairs, with the exception of South African galleries like Goodman and Stevenson being mainstays at the ‘blue chip’-fairs. The Armory Show tried an ‘African’ section a couple of years ago, but nothing permanent happened. Now in 1-54’s 9th London edition – after having branched out to New York, Paris and Marrakech in the past years – there is still an underrepresentation of galleries from Africa at the big fairs (again, this year there were only galleries from Cape Town and Johannesburg at Frieze). Individual artists however are increasingly finding their way up market. A big solo show by Ghanian artist Ibrahim Mahama at White Cube’s Bermondsey location is a telling proof of this.

Ibrahim Mahama, ‘Capital Corpses’, 2019-2021 @White Cube Bermondsey

Still 1-54 remains an important hub – even after almost ten years – for seeing ‘African’ art. The question however is where the fair is going. Somerset House is an enigmatic location, right in the heart of London, but it has its downsides. It’s a labyrinth, rooms are small (sometimes even crammed) and it is difficult to really enjoy the big works. The plus is that it is an intimate fair. 1-54 at Somerset House is like Liste at the old brewery in Basel, with the exception that Liste is a ‘step up’ fair – a gateway for young talents (artist and gallerist) – and 1-54 is more a means in itself. 1-54 used Christie’s in Paris as venue for its 2021 edition in the French capitol, with a more museum-like presentation, giving more space to the artworks to be seen ‘in their own right’.

Having three editions in three cities, 1-54 came up with the idea to create a ‘yearbook’ encompassing the galleries and artists in all three fairs. It is a great almanac, giving insight into the rich offerings of the African art scene – although it focuses almost exclusively on painting, drawing and photography, a general ‘handicap’ of the fair. It shows that ‘portraiture’ – in any shape or (colorful) form – is a prominent feature in contemporary African art. You can’t help but think that this ‘trend’ comes on the heels of the success of African American artists like Kerry James Marshall, Kehinde Wiley, Jordan Casteel and Mickalene Thomas.

Of course, in a fair that has so much to offer, there are numbers of interesting artists to be found. Omar Mahfoudi (Marocco) at Afikaris is an interesting talent. His blend of portraiture and abstraction offers intriguing paintings of people in an intermediate zone. Sahara Longe (UK) is a real talent at Ed Cross Fine Art with her figures playing on art historic references (replacing while role models with black figures).

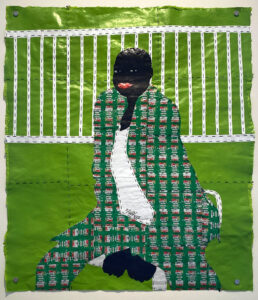

Rufai Zakari, ‘Flex on My Seat’, 2021 @Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery at 1-54

Rufai Zakari (Ghana) at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery is working in the tradition of the contemporary depiction of black figures in contemporary art, but gives his own twist. [[05]] A pleasant surprise are the paintings of Zanele Muholi (South Africa), who is more known for her photographs, but intrigues with expressive portraits.

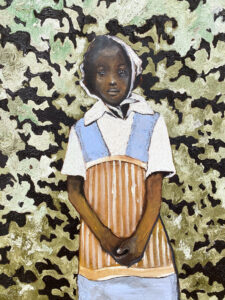

Zanele Muholi, ‘Khalima’, 2021 @Galerie Carole Kvasnevski at 1-54

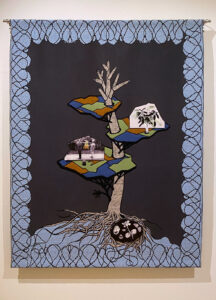

Otobong Nkanga, ‘Contained Measurres: Kolanut Tales’ (detail), 2012 @We Are History at 1-54

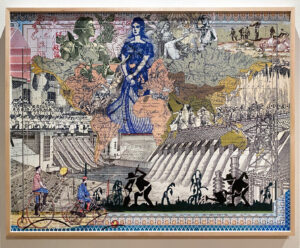

Shiraz Bayjoo, Dan Sa Karo Kann (in those cane fields), 2021 @We Are History at 1-54

Part of 1-54 is the exhibition ‘We Are History’ curated by writer Ekow Eshun. It connects the legacies of colonialism to the global climate crisis with artists like Otobong Nkanga (Nigeria, a tapestry in her signature style, mixing abstraction, figuration and collage), Shiraz Bayjoo (Mauritius, a complex installation including fabrics, found objects and small paintings in rococo-frames referring to Dutch colonial imagery of the savaging of the lands they ‘conquered’) and Carolina Caycedo (UK, an allegoric representation of a ‘snaking’ river). Malala Andrialavidrazana (Madagascar) also exhibits at Dominique Fiat Gallery and – through collage – redraws colonial maps with a multilayered message cross-referencing colonial exploitation and geographic locations. ‘We Are History’ is a real asset to a fair that is diverse and eclectic. The special project by Lakwena Maciver (UK) is a colorful affair finding expression is graphic designs of patterns and texts. [[11]]

Carolina Caycedo, ‘Serpent River Book’ (detail), 2017 @We Are History at 1-54/Malala Andrialavidrazana, ‘Figures 1852, River Systems of the World’ (detail), 2018 @We Are History at 1-54

Lakwena Maciver, ‘Nothing can Separate Us’, 2021 – Special Project at 1-54

Outside of 1-54, the London Art Week centering around Frieze made clear that African American art has solidified its position as a strong presence on the art market. There was quite a bit on offer at the main fair (solo stands of Deborah Roberts at Stephan Friedman and Glen Wilson at Various Small Fires, but more telling were the exhibitions at prominent galleries around town.

Deborah Roberts @Stephan Friedman at Frieze 2021

Glen Wilson @Various Small Fires at Frieze 2021

Christopher Myers, ‘Whipped Peter and the Bronzes’ (detail), 2021 @James Cohen at 9 Cork Street

Frieze introduced an off space at 9 Cork Street this year, where James Cohen showed Christopher Myers. His fabric paintings fit in a recent trend of woven/sewn works. Diederick Brackens is a prominent current example of this kind of works and Myers finds his own ‘language’ with his bold portraits.

Noah Davis, ‘Mary Jane’ (detail), 2008 @David Zwirner

Presentation Underground Museum @David Zwirner

David Zwirner connected with the estate of Noah Davis a couple of years ago. The artist who died in 2015, was shown extensively at the New York branch of the gallery in early 2020 and now comes to London, a just homage. His work is a match for painters like Luc Tuymans and Marlene Dumas, who gained prominence in the ‘90s and 2000’s. It was overdue that the oeuvre of Davis landed in the top spots in the art world. On the top floor of Grafton Street there is a tribute to the Unground Museum in LA that Noah Davis co-founded and were he curated some fascinating shows on for example abstraction (shown in the form of maquettes).

Torkwase Dyson ‘Liquid A Place’ @Pace

At Pace in Hannover Square Torkwase Dyson presents three large sculptural volumes in a side space (with an overview of around 20 small scale Rothko paintings upstairs). The work mediates between architecture and painting, where the three objects are both sculpture and space for performance. Her focus is environmental issues and spatial liberation in relation to the black body.

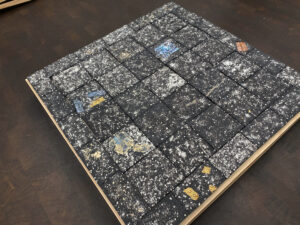

Gagosian put on a show curated by Antwaun Sargent called ‘Social Works II’ at its Grosvenor Hill space. Central to the exhibition is ‘the relationship between space – personal, public, institutional and psychic – and social practice’ by artists from the African diaspora. This is explored in artworks that are both explicit in their references to the ‘real’ world as abstract. Alexandra Smith ‘deconstructs’ the female black body into abstracted shapes arranged on a plane, almost like theatre sets. Kahlil Robert Irving pressed traces of discarded objects into black ceramic tiles, creating the mirror image of a pavement – and a ‘night sky’ – as a podium for (troubled) daily life.

Alexandria Smith ‘Here Comes The Sun’, 2021 (left) and ‘Set Adrift on Memory’s Bliss, 2021 (right) @Gagosian Grosvenor Hill

Kahlil Robert Irving, ‘Millennia – (through space and street)’, 2021 @Gagosian Grosvenor Hill

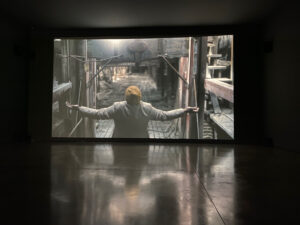

Both Whitechapel Art Gallery and White Cube Mason Yards put up a solo presentation by Theaster Gates. Both exhibitions center around Gates’ fascination with clay. At Whitechapel we see a comprehensive overview of objects, installations, documents and a film in which Gates explores the material for its (historical) cultural significance and ‘practical’ use, from vessels to bricks. We see clay objects from his own collection, from museum collections and from colleagues, there is a whole room with his big size objects (clay vessels on self-made wooden plinths, paying tribute to both the Japanese sculptor Noguchi and the Romanian sculpture Brancusi, acknowledging modernist traditions in sculpture) and there is a film – dubbed ‘A Clay Sermon’ – in which Gates mixes past (clay)performances that are often rooted in jazz and fragments of him performing in a derelict brick factory (the Western Clay Manufacturing Company in Montana). This is an in depth show that gives insight in the significance of clay as a ‘labor’ material, it’s connection to colonialism and global trade and its ritualistic aspects. The film at White Cube Mason Yards focuses on Gates chanting – like a ‘priest’ – in the almost surreal dilapidated brick building in Montana, repeating phrases like ‘feel the fire burning in my soul’. Powerful in all its directness.

Theaster Gates ‘Oh, The Wind’, 2021 @White Cube Mason Yards/ Overview recent clay sculptures @Whitechapel Art Gallery

And then there is the show of Haitian artist Hervé Télémaque at the Serpentine Galleries. The artist left his homeland for Paris in the 60’s and adopted a pop art-like imagery in which he reflects on both the history of his country and political events of the time, including issues of race. In several works Télémaque pays homage to historical figures (like Haitian painter Hector Hyppolite). In one of the works there is a tribute to Jacob Lawrence, even including his signature, as the past master of the depiction of social issues.

Hervé Télémaque, ‘Le voyage d’Hector Hyppolite en Afrique’, 2000 @Serpentine Gallery

One thing is for sure during Frieze 2021: artists of color were ‘everywhere’ in London. 1-54 has its own place in that framework.

Robbert Roos is director of Kunsthal KAdE, Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

Photos: Robbert Roos