In Nirit’s oeuvre, identity and existence are two complex issues, both of which define the being of the Ethiopian-Jews. On the one hand, they are bound to Israel through their religion, and on the other hand affiliated to Ethiopia through their appearance.

Enos Nyamor on the Ethiopian-Israeli artist Nirit Takele

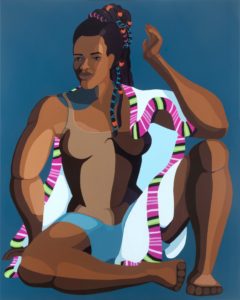

Figure in shape, 2020

The Work of Nirit Takele

In search of Homeland

It was an inevitable mission: Israeli Air Force and chartered commercial aircrafts hovered above the Addis Ababa skyline, and by the end of the operation, about 14,500 Ethiopian-Jews had been evacuated. The third aliyah mission, the repatriation of diaspora Jews towards Jerusalem, had been a success. By the end of Operation Solomon, only a thousand Ethiopian-Jews remained in the then war torn Eastern African nation, mostly trapped in rebel-held territories. Initial encounters, upon landing in Israel, were shrouded in ecstasy and jubilations. But thirty years later the Ethiopian-Jews are entangled in a struggle for identity, and it is this entanglement that pervades Nirit Takele’s work that was on view, as part of the exhibition You Belong Here, at the C24 gallery in New York City.

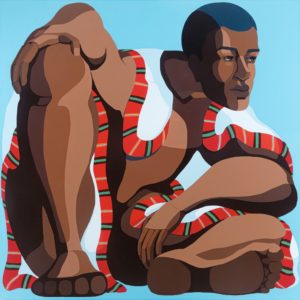

Still, to engage Nirit’s work, it is necessary to confront what is presented on the surface of the canvas, and which is the intricate blend of figuration and abstraction. Of her six paintings on display, the appearance of figures, in various postures, dominate the canvas. These figures occupy most of the space in the canvas, with only the margins left without, and in return, these figures are formed through a contrast with a background of a uniform gaudy color of flat brushes. These colors range from sky blue to pink to turquoise. Only through the figures in her paintings does abstraction gain a currency. This abstraction quality is less about the use of imaginative forms—those shapes that are amorphous—but more towards the exaltation of the figures that appear, almost astral in nature. For instance, when looking at Nirit’s Big Man, 2020, there is an awareness of staring at a larger than life figure. The fingers of this figure, captured through a variation of color intensities, are reminiscent of observing an elevated figure, almost kingly in stature.

Big Man, 2020

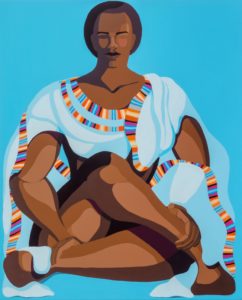

Extending this elevation, this abstraction captured through Nirit’s colorism, is the superimposition of colored strips around the figures. According to Nirit, these strips are embodiment of her Ethiopian heritage. Indeed, anyone who is conversant with the Ethiopian traditional dress, especially the Habesha Kemis, will instantly recognize the affiliation to Nerit’s conceptualization. These strips are of varying patterns and are perceptible in most of the paintings on view. Like robes, these strips encircle the figures, and in a subtle way, enhancing the appearance of the figures. In Figure, 2020, the subject sits in the middle of the canvas, the strips, hemming the moon-white shawl, flow around the figure. Yet still there is the almost string absence of overt facial expression, and it is in this voluntary omission of details that Nirit’s abstraction flourish. In place of the figure’s eye, for example, is a splotch of maroon, and the rendering technique is almost cubist.

Figure, 2020

In spite of the appearance of color in conveying abstraction, it is the grounding of her figures in the chocolate or brown skin textures that become the trope for the identity crisis in Nirit’s work. As mentioned, all these figures are elevated. They are presented almost as kingly, emitting unsurpassed confidence. But the condition she portrays is paradoxical to the reality that Israeli-Ethiopians face, despite their faith. Their Jewishness is still under constant doubt. It is as if their identity ranks at the bottom of the Israeli society. Nirit perceives her dark-skinned figures to be an act of disrupting the dominance of light-skin in Israel art. Her work is projecting the subaltern of the Israeli society into the visual repository, hyphenating the cultural landscape with the often intimidated subculture.

One way of approaching this show is by examining the ontology—the nature of being—of the Ethiopian-Jews, most of whom are now settled in Israel. Nirit was born in Ethiopia in 1985, and was airlifted during Operation Solomon. The origin of the Ethiopian-Jews is ambiguous, but an article that appeared in the New York Times, shortly after Operation Solomon, notes that “according to their own legend, the Ethiopians are descendants of the progeny of King Solomon, who built the First Temple, and the Queen of Sheba. Other scholars believe they are a part of the lost tribe of Dan.”(1) But then, what constitutes the true identity of the Ethiopian Jews? In his text Being and Time, Martin Heidegger refers to the fundamental problem of identity. He writes, “being consists in not determining being as beings, by tracing them to origins in another being.”(2)

Beating the Israeli soldier, 2015

In Nirit’s oeuvre, identity and existence are two complex issues, both of which define the being of the Ethiopian-Jews. On the one hand, they are bound to Israel through their religion, and on the other hand affiliated to Ethiopia through their appearance. And it based on their appearance that they face undue discrimination. One of the works on display, and perhaps the largest of the pieces, is Beating the Israeli soldier, 2015. In the painting, rendered in Nirit’s characteristic style, the Ethiopian-Israeli soldier, whose uniform is torn from the struggle, is smothered by three police officers. This painting was inspired by a real event in 2015, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, and led to violent protests in Israel. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu later apologized to the young soldier, Demas Fikadey.(3)

But the condition of the Ethiopian Jews, in their struggle for belonging, reflects the universal challenge of most migrants around the world. Those who move, in the words of Vilem Flusser, the Czech-born writer, lose their homeland, and so become unsettled.(4) And this unsettling experience is followed by an orientation, an act of configuring oneself. But this process, as evident in the case of the Ethiopian-Jews is impeded by existential differences, by such attributes as the color of one’s skin. A year after Demas Fikadey’s victimization, responding to the press on the profiling of Israelis of Ethiopian origin, the Israeli Police Commissioner Roni Alscheich said that “This was the case in all the waves of immigration [to Israel]. When there is a community that is more involved in crime—also with regard to Arabs or East Jerusalem, and the statistics are known—when a police officer meets a suspect, naturally enough his mind suspects him more than if he were someone else. That is natural.”(5)

Orit Ben Shitrit, Malevolence Glittered Pupils, 2017

Nirit’s series of colorful paintings was, at the same time, hyphenated by Orit Ben Shitrit’s dystopian pieces, but these were almost marginal, merely supplementing the intense conversation that Nirit’s work provoked. Orit is a multimedia Moroccan-Israeli artist. Occupying a corner of the gallery, Orit’s video loops and photographic collages presented an additional problem faced by Israeli’s of African origin. Orit’s work was a grotesque superimposition of found footages, in a style that gravitates towards surrealism, towards the terror of belonging to a place that appears strange to one’s own identity. Among Orit’s work, it is Malevolence Glittered Pupils, 2017, a photo collage of furs and rope and a nose that resonated to Nirit’s engagement with belonging. This particular work was a reflection on imagination as the place for refuge. Even then, the conversation between the works of these artists could thrive if they were separated, and each presented within its context. It is true that they both confront archetypes of alienation, but are also distinguished by separate ontologies. After all, the experience of Ethiopian-Israelis is palpable than that of the Moroccan-Israelis, who, in one way or another, are light-skinned.

Stretching leg, 2020

In the end, Nirit’s work was a search for a new reality. It was simultaneously an act of forging and breaking a chain of disillusions. It was an expression of an inescapable alienation, in which one belongs neither here nor there. Perhaps, it is worth approaching the alienation conveyed through the filter of unarticulated memory, of transnational identity, or even defacement. For Nirit was only six years old when her family emigrated to Israel, and, like many Israeli-Ethiopians, she is still in search of a homeland.