‘Against the Grain’ and invisibility

The opening passages of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man introduce a nameless protagonist to the reader. We come to learn in those first pages that the eponymous character cannot be seen by others because of a “matter of construction of their inner eyes”. Such a condition has motivated the protagonist to seek refuge underground. In this hole, underground, he escapes the darkness which would render him unseen above the surface. Underground, his hole is “full of light”.

Ellison’s description of alienation under white supremacy, what some writers refer to as black existentialism is certainly instantiated by the subject matter in Against the Grain. The exhibition, comprised of black and white photographs documents the consequences of racism on the psyche and being of blacks. This procedure recalls Ellison’s interplay on light and darkness, visibility, and invisibility but there is no metaphor here. In The Camera is not a machine gun, David Goldblatt reminds us that “during those years color seemed too sweet a medium to express the anger, disgust and fear that apartheid inspired”.

In Against the Grain, black and white become critically integral toward explaining race/ism, not as metaphor so much as the very means through which sight and more specifically the “gaze” is organised, regulated and enforced under white supremacy. Against the Grain refers us to the ideological rudiments responsible for producing sight as an interpretive schema and demonstrates the reasons as to why race is a suitable analogue for conceptualising the pictorial grain. Race is precisely that atomic gradation of an image which produces what can ultimately be seen or unseen.

Like Ellison’s prologue, the exhibition attempts to expose the paradoxical division between life above the surface and life underground, between light and darkness but through a realism absent in Invisible Man. Instead, the series of photographs reveal the consanguinity between these two worlds derived from a racial and capitalist order. Life above the surface is dug from the very same “Lashing” shovels retrieved from underground. The scopic regimes which would render black people invisible are not a consequence of a ‘matter of construction of white people’s inner eyes’. For example In Ernest Cole’s ‘Untitled’ House of Bondage, we see that invisibility is not figurative. Instead, young black men’s faces are made unrecognizable, ‘invisible’ because of the sheer darkness of the holes they inhabit.

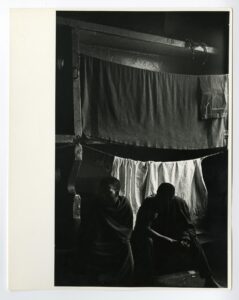

Ernest Cole, Untitled (from House of Bondage), 1960

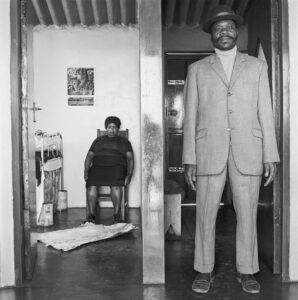

David Goldblatt, Man with an injured arm, Hillbow, 1972/George and Sarah Manyane, 3153 Emdeni Extension Soweto, 1972

This realism appears again in the work of David Goldblatt, whose work unmasks the artifices of opportunity and progress under Apartheid. The photographs of a Man with an injured arm, Hillbrow and George and Sarah Manyane, 3153 Emdeni Extension Soweto deform the signifying properties of the ‘suit’ respectively. The suit’s civilizing content is parodied by the context in which it is expressed. In the former, an injured arm is concealed by the lapel of the suit. The suit, dignifying as it may seem, cannot conceal the extent of the injury to the man. In the latter, the pictorial elements contradict one another across the visual plane. The suited man stands with a resigned expression on his face separated by a wall from the view of his seated (presumably) wife. The woman looks at the camera with a hapless foreknowing of the very image which she cannot see. The suit(standing) is foregrounded in the photograph, but it is her expression(seated), almost far enough to be out of focus which tells us precisely what it means or doesn’t.

In Ruth Motau’s work, we are taken into the quarters of women’s hostels, churches, and dance groups, glimpsing what Ellison refers to as the ‘illumination of blackness’ invisibility’. Motau’s photos reveal the stagings of resistance that take place underground, made possible through the preservation of black cultural life. Despite the harrowing conditions these women and men are forced to endure, community survives. In this series, the darkness which had obscured the faces photographed by Cole is at once illuminated. In this darkness, Motau restores the interiority of the figures who are effaced by shadows. We are made to witness the cultural impetus that directs one’s capacity to survive, from the playful rehearsals of friendship to the communion enabled through ritual and ceremony. In Motau’s photographs, black people may very well be invisible, but they are not in the words of John Keene, ‘dark to themselves’.

Woman sitting on the bed with a friend, 1991

The legibility of these historic photos (Cole, Goldblatt and Motau), taken at different points during Apartheid, from segregation to the dysfunctional years of South Africa’s transition is further punctuated by the work of Lindokuhle Sobekwa, who recalls the intransigence of a violent past even where its symbols (e.g slegs blankes) are absent in today’s constitutional democracy.

Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Death of George Floyd, 2020/Mzwandile at home, 2019

Sobekwa’s work takes place in the same world of Ernest Cole’s 70 years later and yet the subjects in his photographs are marked by the same veiled figuration. To borrow from Hortense Spillers, it is “as if time nor history, nor historiography and its topics, shows movement”. Read together, the work of the 4 South Africans expose a world which cannot be dislodged from its white supremacist foundations despite the universalizing of civil liberties. The spatiotemporal configuration of the present, what some refer to as “post-apartheid” is shown to be a reconstruction of the violent rationalities which are responsible for the making of South Africa. The photographs testify to what Derrick Bell refers to as ‘the permanence of racism’.

It is in the work of Ming Smith, the only American photographer that the exhibition appears to veer from the focus of its presumed object of study. With the exception of Mother and Child, the routine and quotidian scenes of black life as well as the repressive and constricting environments which typify the other works do not feature here at all. Instead, Smith’s work (although dealing with race) is marked by the conspicuous re-appearance of the American flag. It appears as a thematic and symbolic device, situating the meaning and context of race and as the photos of the Bicentennial exemplify, the meaning of freedom too.

In the work of Smith’s South African counterparts, it is the documented experiences of black South Africans, the brutish and indiscriminate conditions of racism which conjure the symbols that are responsible for defining South Africanness. In the same way cotton plantations resurrect the memory of American Slavery, so too have the mines and hostels become a part of the edifying character of this country’s identity. For Cole, Motau, Goldblatt and Sobekwa, the South African flag is not laden with the contradictions that Smith is concerned with exposing. The disillusionment with the significations of the American Flag, what Smith refers to as America seen through Stars and Stripes do not occur here in South Africa. The struggle for black South Africans is not one of recognition or of the opening up of civic life. For black South Africans, the question of sovereignty and of title to territory empty the flag of any possible emancipatory investments.

Ming Smith, Bicentennial Celebration, Harlem 1976/America seen through stars and stripes, New York City, 1976

In this way Smith’s photos are somewhat extraneous. The ideological themes which connect the other works (labour coercion, dispossession, disinheritance) are not available for the same kind of inspection here. Perhaps this extraneity is intended as a comparative exercise, a footnote on the similarity of experiences. In From South Africa to South Carolina, Gil Scot Heron reflects on race and racism’s interrelation in America and South Africa respectively. On the opening track he declares that “You know it’s like Johannesburg, Detroit like Johannesburg, freedom ain’t nothing but a word”. Heron like many of his peers viewed the racism in South Africa as the paradigmatic example from which to interpret their own experience in America. Situated alongside her South African counterparts, perhaps Smith, a contemporary of Heron and a Detroit native herself attempts to tether this historical connection in her photographs .

The inclusion of Smith’s work suggests a similitude between American and South African racism, but it is not sufficiently evinced in Against the Grain. There are connections of course, from Sobekwa’s ‘Death of George Floyd’ to the posters of American pin-up girls in Motau’s ‘Woman sitting on her bed with a friend’ but whether they achieve the kind of intertextuality that Smith’s work ought to prompt is not clear.

What stands out in this exhibition is Goldblatt’s observation that colour is wholly insufficient to describe the devastation wreaked upon this country’s black population, perhaps we too can read Smith’s work here as a rejoinder or post-script. Perhaps the fact that her own country’s flag only appears in black and white recalls Goldblatt’s very own instincts.

Above all, Against the Grain asks us to resist the so called progressivism which would have us unsee race. Instead what the exhibition succeeds in demonstrating is that where we cannot see race, where the picture is too dark to render the image recognisable is precisely the place where black people reside. That invisibility is not just a metaphysical reality but very much a material consequence of being dispossessed of the very means to be seen.