FROM THE ARCHIVE 2: December 10, 2017

Following in the footsteps of their predecessors, this new generation has taken up the social and revolutionary potential of poetry; they have grasped it between two hands, stretched it, pulled it apart, and moulded it back together in their own way, with an array of multi-disciplinary influences from hip-hop, jazz, visual art, film, and performance.

Candice Allison on poetry in South-Africa

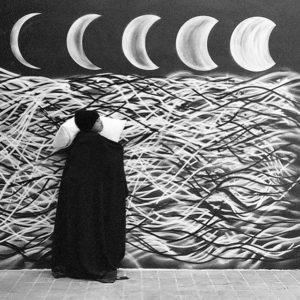

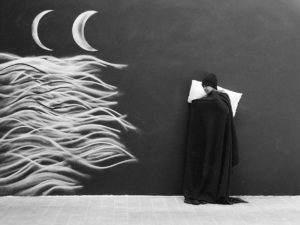

Robin Rhode, The Moon is Asleep, 2015. Super 8mm film transferred to digital HD, duration 1 min 50 sec, images courtesy of the artist and Stevenson Gallery.

There Will be Poetry Here Tonight

I.

there is no light

tonight

no stars

no moon

only this sheath

of night

dark and depthless

as a sorrowing

heart

there is no moon

no light

and you –

you are

no longer

here

Wondering through the dimly lit exhibition ‘The Quiet Violence of Dreams’, in the calm, quiet space of Stevenson Gallery Cape Town, the baritone voice of Don Mattera recites the solemn lines from a poem he wrote to his lover after he passed away from HIV/AIDS in the late 1980s. (1) His words have been visually interpreted by Robin Rhode in a stop-motion video work titled after the poem. The Moon is Asleep (2015), filmed using Super-8 film, depicts a child sleeping standing up against a black wall covered with chalk drawings of the moon and sea. In 2015, Rhode told Interview Magazine, “What drew me to the poem was trying to decipher light and dark… What does that mean when the moon is asleep? Is the moon sad? Is the moon covered in darkness, an eclipse? I was trying to find a formal understanding of what this title means, so I went about creating this animation without being captivated by the backstory; that came afterwards… The poet and I are very close, he’s 80 years old, I met him some years ago, and we’ve been collaborating for some time. I’ve been engaging with his poetry a lot, because of his biography and his personal history.”(2)

Robin Rhode, The Moon is Asleep, 2015. Super 8mm film transferred to digital HD, duration 1 min 50 sec, images courtesy of the artist and Stevenson Gallery.

II.

I am the one

whose bones are strong enough

to carry the weight of two skins

I am the one

whose mouth is supple enough

to hold the secrets of two tongues

no matter who I tell you I am

do not believe me

no matter who I tell you I am

I am always

only

half

of myself

In the opening lines of the woman speaks, the first poem in Toni Stuart’s Krotoa-Eva’s Suite: a cape jazz poem in three movements, she begins to address the various aspects of life that affect women, and her own personal experience as a woman of colour, through her re-telling of the historical narrative of Krotoa, a Khoi woman who, from the age of 10 or 11, lived and worked in the home of Jan van Riebeeck in 17th century Cape Town. She later served as a translator between the Dutch and the Khoi during the cattle wars because she spoke both languages. Her Khoi name was Krotoa, but the Dutch gave her another name: Eva. She eventually married a white settler and was baptised into Christianity. Her children were the first documented mixed race offspring in the Cape.

In collaboration with filmmaker Kurt Orderson, the poem has been developed into a multi-media installation, presented in 2016 as part of the exhibition Re(as)sisting Narratives at Framer Framed in Amsterdam, and the District Six Museum in Cape Town. The work challenges dominant male colonial narrations of history about Krotoa-Eva, as evident in the recent problematic film about her life, in which she is depicted as highly sexualised at a young age, bitterly conceited after she was removed from her position as interpreter and mediator, and a negligent mother because of her descent into alcoholism.

Speaking at the Decolonising Feminism conference, hosted by the Wits Centre for Diversity Study in 2016, Stuart talked about how re-appropriating the female voice in South African historical narratives can open up discursive spaces for re-imagining the “coloured” identity, and also as a way to critically examine the effect and influence colonialism and the colonial way of thinking has had on feminism. “In order to heal, we need to learn how to face these wounds, our wounds, with compassion and love and care… Part of the wound for ‘mixed’ or ‘coloured’ South Africans is that so much of our history has been lost. We are unrooted. We do not know the full truth and breadth of where we come from, and thus who we are.”(3)

III.

“The train has always been a symbol of [loss] … the train was South Africa‘s first tragedy” – Hugh Masekela (4)

South Africa’s social structure has been shaped by mining and enforced migrant labour like no other country in the world. On one hand, the train symbolises a connection between two places, but during apartheid South Africa it simultaneously represented separation as a vehicle that removed miners and migrant workers from their families, while they lived in crowded hostels far away from home. Today, the train continues to symbolise segregation and spatial apartheid – the urban centre of Cape Town still reflects its history as a space “for whites only”, while areas on the outskirts of the City Bowl – characterised by vast formal and informal settlements – continue to divide citizens by race. In Cape Town, ongoing mismanagement and allegations of corruption in the running of this essential transport service has resulted in lengthy delays, severe overcrowding, and high levels of crime. Cue the Metrorail train from Cape Town to Muizenberg as the unusual, yet appropriate stage for poet Koleka Putuma to present her poem ‘Collective Amnesia’ – reflecting on current affairs, grief and memory, pain and joy, sex and self-care, and all that has been forgotten and ignored, both in South African society, and within ourselves – to commuters in the train’s third class carriages; or the train from Cape Town to Stellenbosch where ‘Manufractured’ was presented in collaboration with other performers and visual art collective Burning Museum. (5)

IV.

I feel a poem – Don Mattera

Thumping deep, deep

I feel a poem inside

wriggling within the membrane

of my soul;

tiny fists beating,

beating against my being

trying to break the navel cord,

crying, crying out

to be born on paper

Thumping

deep, so deeply

I feel a poem,

inside

On any Tuesday night in Cape Town, you might wander into The Drawing Room at 8pm, a hide-way little café/creative space in the bohemian suburb of Observatory, and find yourself chatting to the bar man, as you glance furtively over at the lone mic stand keeping company with a pair of speakers in the centre of a makeshift stage – Cape Town is never on time for anything. Poet and writer Roché Kester will rush in at 8:30pm to reassure you: “Yes people, there will be poetry here tonight.” By 8:45pm you will be grateful that you arrived early, as a wave of warm bodies flow into every available chair and empty space around you. By 9pm, the air will be thick with the vibrations of nervous energy. Roché will return to the stage with her List of Names and call out the first poet to open the membrane of their soul and let out the words that have been thumping inside them for days, weeks, or even months.

Don Matera

Grounding Sessions is a weekly poetry event, one of several poetry outfits and festivals – including Urban Voices, Poetry Africa, Badalisha Poetry X-change and podcasting platform, InZync Poetry Sessions, Lingua Franca and Poetica, to name a few – who are keeping the tradition of poetry very much alive in Cape Town and across South Africa; while also cultivating an appreciation of South African poetry around the world. The setup is an open-mic type event, with a featured poet each week taking the audience on a lyrical journey of rhythm and verse. The poets who have worked up the courage to put their names down on the open mic line-up are mostly young, often gifted, usually bold, and sometimes shy. Some capture the audience with their natural poise, perfectly timed delivery, and the beating passion of their words. Others might have the audience leaning in, closer, closer, to hear the words quietly uttered from their lips for the very first time.

Events like these are nurturing incubators for a new generation of poets who have found that they can explore difficult subjects, pain, and the day-to-day grind of life, through their prose. Their words provide a window into the zeitgeist of our time, and right now, the kids have found a voice and they are demanding to be heard. They’re talking about pay-back-the-money and minimum wage politics; they’re shouting about black mother’s cleaning white floors, black lives matter, and fees must fall; they’re defending LGBTQ rights, women’s bodies and female empowerment; they’re calling out sexual harassment on the streets, in the workplace, in the sanctity of the home; they are asking: Who wrote our history? If Jesus was black, would he save us? Why are we learning about Shakespeare, Shelley and Keats in our schools when we have Diana Ferrus, Don Mattera and James Matthews?

Grounding Sessions, © photo Matthew Warely.

V.

“South African poetry rests in the mine, the campus, the workplace, newspapers, journals, the web, slim volumes, anthologies, tiny rooms or cells or elsewhere..” – Marian De Saxe

South African poets have an active and vigorous history of speaking their mind through prose. While records state that written literature by black South Africans only emerged in the 20th century with mission-educated writers who celebrated and reclaimed ignored African histories, languages and cultures, this does not reflect the reality of a rich tradition of oral storytelling. Some of these stories were historical legends, like the story of Nongqawuse, a Xhosa girl who convinced her people to slaughter all their cattle after she dreamed that this would rid them of the White people settling, uninvited, on their land. Others were tales which explained nature and how the physical characteristics of animals came about, while also carrying moral warnings, such as the San tale of how Mother Moon split the hare’s lip because he didn’t listen properly. Since the 1970’s there have been vigorous African literary debates about whether the true representation of South Africa in literature was oral or written; either way, what these confirm is that literature in both forms has forged a close relationship to politics, informing many domains of public life and abundant African schools of literary criticism.(6)

From 1948 to 1990, poetry flourished in spite of violent oppression and censorship in apartheid South Africa. The Drum writers and associated poets of the 1950s – including such names as as Peter Clark, James Matthews and Richard Rive – reflected a new generation of black authors depicting a pulsating urban black culture for the first time. The 1960s witnessed a radical shift with white Afrikaans writers like Breyten Breytenbach and Andre Brink beginning to produce increasingly politicised work in response to draconian laws designed to separate blacks from whites. In many parts of the world, the 1970s saw an upsurge in political expression via song, poetry, theatre or performance. Throughout apartheid South Africa the African National Congress (henceforth ANC) invested particular political agency in the production of poetry.(7) Songs and poems multiplied, particularly with the formation of the Black Consciousness movement, with protest poets taking the platform to rouse audiences at underground events across the country. As the Government‘s physical destruction of large, settled urban areas in South Africa attempted to destroy historically unified communities, poetry became a potent means of recording and engaging with a vanishing past. Continuing through the 1980s, the strongest voices in poetry came from ‘worker poets’ associated with the trade unions.

Koleka Putuma, ©photo Andiswa Mkosi

As apartheid gradually came to an end in 1994, many have described the 1990s as a ‘honeymoon phase’ for literature, as poetry mirrored Mandela’s sentiments for a peaceful transition to what was widely touted as the ‘rainbow nation’. Contemporary poetry, it seems, is revealing the widening cracks in South Africa’s ‘arranged marriage’ of politics and culture. That is not to say that a divorce is on the horizon, but like many 21st century matrimonies, traditional marital roles are shifting, while the kids are unashamedly, unapologetically, telling us that they want their parents to deliver on the promises made during the rosy haze of newly wed bliss. As Koleka Putuma, winner of South Africa’s first national slam poetry competition in 2014, describes it; she and her peers are trying to start an “honest-to-God-truthful conversation” about the hard issues South Africa still needs to face.(8) Following in the footsteps of their predecessors, this new generation has taken up the social and revolutionary potential of poetry; they have grasped it between two hands, stretched it, pulled it apart, and moulded it back together in their own way, with an array of multi-disciplinary influences from hip-hop, jazz, visual art, film, and performance.