Purnaa Deb’s work stands at the intersection of grace and redemption and looks at what is possible. She explores the liminal space between chaos and order.

Fadzai Muchemwa on the work of the Johannesburg-based Purnaa Deb

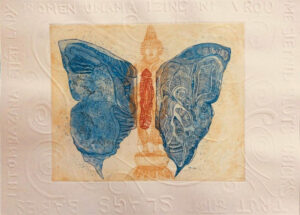

The beauty within, 2019

In-between Sky and Garden: Purnaa Deb’s Exploration of Yearning and Groundedness.

And the air was full of Thoughts and Things to Say. But at times like these, only the Small Things are ever said. Big Things lurk unsaid inside. – Arundhati Roy. The Goddess of Small Things

Purnaa Deb’s body of work Between Sky and Garden is both personal and universal. Purnaa demonstrates in her exploration of the integrated worlds of nostalgia and groundedness that memory resides nowhere and everywhere in an intimate account of her experiences as a migrant and an artist working during a pandemic.

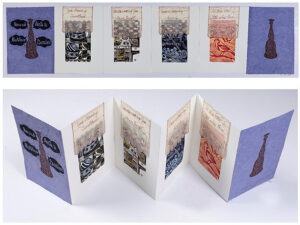

Purnaa mainly uses print medium, with appliqué, embroidery and drawing to create this body of work. There are several layers to the issues that Purnaa addresses. Her work investigates identity through the dialectics of the self and society and explores the social, political and personal interface. The position of women in society, the isolation brought on by the pandemic, migration, which Purnaa refers to in Changing of Address, the covid crisis in India, with all of its prevailing prejudices of religion, caste, and class, but also, more widely, how authoritarian state governments have turned in the face of the pandemic and aspirations for a better life.

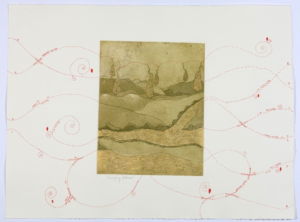

Changing of Address, 2017/Between Sky and Garden project

The title seems fitting. The sky represents infinity, eternity, immortality, and transcendence; it is the residence/abode of the gods; it is omnipotence whilst the garden symbolises groundedness and an image of the soul and innocence.

The sky also is symbolic of order in the universe. It is an endless entity waiting to be explored. It is about going home. Purnaa has spoken about the sky, representing how she got to South Africa and can travel back home. It is beyond the mind, and the senses cannot grasp it. From the whimsical What is Cloud? What is Air? the sky is also the source of rain, making plants grow and feed us.

The garden is the revolutionary symbol of the sacred and encourages contemplation, growth and expansion. The garden is limited on the horizontal plane, but it is boundless on the vertical plane, toward the sky and depths of the earth. It links heaven and earth, mundane change and eternal permanence.

Stuck between the whimsical and the real, Purnaa, through her art works, creates a courtyard/garden through which we can explore her practice and experiences. The courtyard is the place for meeting the outside and the inside, the public and the private. It is also a portal through which we can travel to other worlds, making cognitive and emotional space for listening, looking, and articulating our desires. You can view Purnaa’s work without necessarily knowing anything about her experience. Purnaa asserts herself as a ‘goddess of small things’ (1) in how she explores the small things that affect people’s lives and in how her scale, reminiscent of Indian miniature painting (which she was fascinated with at the beginning of her studies as an artist), packs a lot of detail and texture to explore issues that seem small but are pretty vast and confounding.

Bread Butter and Desire, 2017

You can feel a yearning for the home she left behind; she sees reminders of home in small things and a determination to make a home where she now finds herself. The bits of lace from a frock her mother made for her when she was young, the lace curtain which used to hang in her mother’s kitchen now used for embossing and printing in her work; mementoes of a time she clings to in an unfamiliar world. She carries the goddesses from the old country with her and the space for attention which looks a lot like a prayer she gives the goddesses in her work, has her hopes and aspirations. Yakshi, the guardians of the treasure hidden in the earth, are referred to in A Goddess and two wings. Lakshmi/ Lakkhi (which means proneness in Bengali) is the goddess of wealth and happiness and is referred to in from Johannesburg to Kolkata, where the handstitched Kolkata and Johannesburg skylines sandwich the appliqued motifs of the goddess.

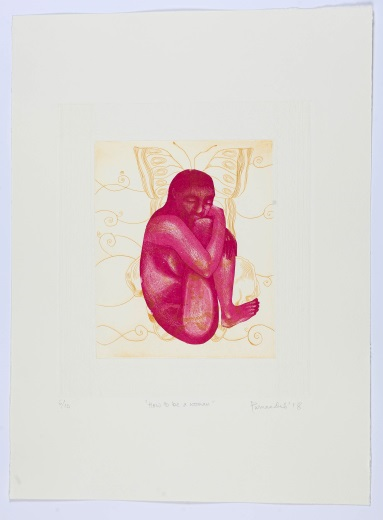

How to be a woman, 2017

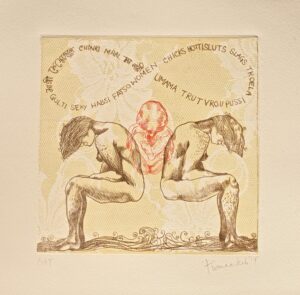

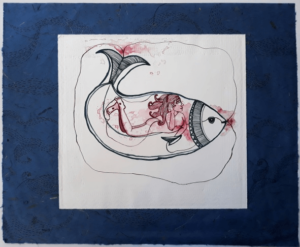

A Fishy Tale, Growing Together and How to be a Woman point to her encounters as a new wife moving to a new country are pretty personal. The transition from living in her parents’ house to staying with her inlaws and living in Johannesburg is an example of frontiers she has had to cross in an ever-evolving world. For work like Name Sake, she moves from personal to universal. “I strive to explore the interface between social, political and personal by looking into all the prosaic ‘names’ that we consider general and, in turn, that delineate our identity. This work is a cross-pollination between these banal name-callings of my sphere and the references subtracted from larger peripheries and discourses on tradition, politics of identity, memory, grief, nostalgia and complexities of urban life. ”(2)

Name Sake, 2019

She is nostalgic about the land she left behind but is not romantic about reality. For example, Midday Meal is a scathing commentary on the economics of exclusion that the pandemic exposed and details the Indian Government’s disastrous response to the covid pandemic. This work is incredibly relatable because it addresses the global politics of inequality and exclusion, which reared their heads when lockdowns were implemented across the globe. In painstaking detail, she draws a father with a child on his shoulder, a man leading a goat whilst weighed down by a load and various other trekkers (3) who left the cities on foot to go to their homes in the rural areas when the lockdown was imposed and the public transportation system ground to a standstill. Many died from hunger or exhaustion on their long march home from cities when the lockdown shut down businesses, and they faced the scourge of unemployment and the wrath of the police when they were found violating lockdown restrictions. The world watched gleefully (4) in the comfort of their homes when the police caught citizens trying to feed their families and were made to perform humiliating pantomimes or downright abuse.

The Tale of Quests project, 2019

You are what you eat is social and political commentary and moves from the sensual to the confrontational. Food reminds one of where one comes from, like the fish that remind her of Kolkata, but it is also a source of the inequalities that Purnaa started noticing when she arrived in Johannesburg. When she crossed the frontier and became a migrant, and everything was unfamiliar, she started seeing the gaps brought on by lack of access. One is reminded of the unrest ongoing worldwide, fuelled by job losses and economic inequality. And the impending global crisis brought on by the war in Ukraine.

We are living in frontier times fated to cross not just space but time. Over a year ago, Arundhati Roy wrote of the world standing on the precipice of change and how the pandemic was a ‘…portal, a gateway between one world and the next.’ We have no idea how the world will look after the pandemic. Or if the economic exclusion that is giving rise to protests and riots will be resolved. Those are frontiers we look to cross.

Purnaa Deb’s work stands at the intersection of grace and redemption and looks at what is possible. She explores the liminal space between chaos and order. The calm and meditation that comes with an experimental printmaking practice in service of bodies beg one to ask how small actions can offer new narratives. So what happens when you leave your old life behind? Purnaa steps away from the stricter bounds of printmaking practice, perhaps searching for transformation and belonging and confronting the uncomfortable and engaging with the potentially politically contentious to show us what it means to live in the present in the shadow of the past.