Most of the artists in this lot are locally consumed and no where on the international art scene. Apart from Sanaa Gateja, the rest wouldn’t be masters in the eyes of Simon Njami. Njami is right and there is a need for Ugandan practitioners to play at the big stage because there isn’t much the industry at home can offer. And also, is technique and aesthetics enough to bestow the title of master on one? What happens to the narrative, the stories around us, the pressing issues around us?

Matt Kayem on the discours: who can be called ‘master’?

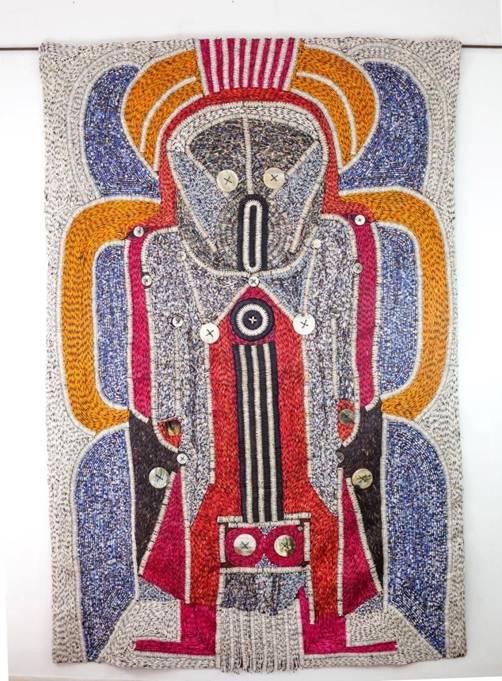

Sanaa Gateja

Seniority First?

On Mastery And Techniques in Ugandan art.

An exhibition to continue the ‘masters in Uganda’ conversation that was put upfront during the 2018 Kampala Biennale opened at Afriart gallery’s larger space in the industrial area of Kampala.

*

Fast backward, the Kampala Biennale of 2018 ignited what became a heated debate by eliminating Ugandan art bigwigs among the line up of acclaimed international artists who were to pass on knowledge to the young ones. The statement that was made by Simon Njami , the curator of that biennale is now being refuted by Daudi Karungi who put together Seniority First. The title, a little provocative, seemingly insinuating that before we deal with anything else, let’s look at the seniors, in this case, the senior artists. The seniors are five Ugandan contemporary artists: Taga Nuwagaba, Fred Mutebi, Stephen Gwoktcho, Dr. Lillian Nabulime and Sanaa Gateja. The exhibition focuses on Daudi’s main interests as a gallerist – mediums and techniques. The five artists come from an older generation, probably the second oldest living one. The older one gathers names like Kefah Sempangi and Hussein Kyanjo.

The five artists are from different artistic backgrounds, four of them have had their art education from the Margaret Trowell School of Art at Makerere University. It’s only Sanaa who’s not an alumni of the institution. Art education was another area to converse about at the opening of the exhibition when Fred Mutebi made a sweeping statement that art was introduced to us (Africans) by foreigners. He insisted that formal art education and practice was introduced in the region by the lady, Margaret Trowell who started up the school at Makerere. Taga didn’t agree with him at first and informed him how art has always been part of our living here even before colonialism.

Power, Sanaa Gateja, 2018

Daudi with this exhibition and his fascination with technical competence puts him in line with the current trends and wave in contemporary art. The art world has stepped back a little before the wild 1930s, before Dadaism, avantgarde and expressionism and we are seeing a return to dexterity and conventional control of material and technique. Key players on the scene today put emphasis on technique in their practice, from Damien Hirst who actually started out with an avantgarde approach, Kehinde Wiley, Njideka Akunyili Crosby to El Anatsui, to mention but a few. This could also be the reason for the rise of black figuration in the art world which has seen the making of art stars like Paul Ndema, Ian Mwesiga, J.P Mika and Jeremah Quarshie.

Rumour mongers 1, terracotta, 2019, Lillian Nabulime.

When you enter the gallery, your eyes could be stolen first by the magnificent tapestries of Sanaa Gateja for their proximity to the entrance and them being the biggest works in the collection. Sanaa’s paper bead treasures fit well on the international art scene for their inventiveness and uniqueness but also for étheir synchronization with the works of other African giants like El Anatsui, Abdoulaye Konaté and Serge Attukwei Clottey. Sanaa trained as a goldsmith in Florence, Italy and the use of design principles most especially balance can be seen in his tapestry work. The weight in Sanaa’s work lies in the time spent making a piece which is usually five feet squared or a foot less. From rolling the paper beads and weaving them together, it’s surely work that requires many pairs of hands which Sanaa finds in women around his neighborhood. The tapestries on bark cloth hold both personal and societal issues and stories. He says his current project explores a wide theme, ‘The African Journey,’ which deals with aspects of African history as a journey.

*

Dr. Lillian Nabulime, also one of the two lecturers from Margaret Trowell School of Art at Makerere in this exhibition showed 13 terracotta pieces from her Rumour-monger series. Nabulime is known for her wood carved sculptures that are usually large but for this show, she goes miniature with these one foot terracotta works. The sculptures are of human heads in her signature semi-abstract style similar to the primitive kind from ancient African artifacts. Grotesque, wide eyed and open mouths, they tell the story of those that spread rumours. You have to love the play, drama and openness in Nabulime’s sculpture which also comes out when she stands up to talk. Speak of true artistry, one that transcends the canvas or the studio but also projects through the creator’s persona. Nabulime’s work often deals with social life, politics, gender, race and epidemics especially the HIV scourge.

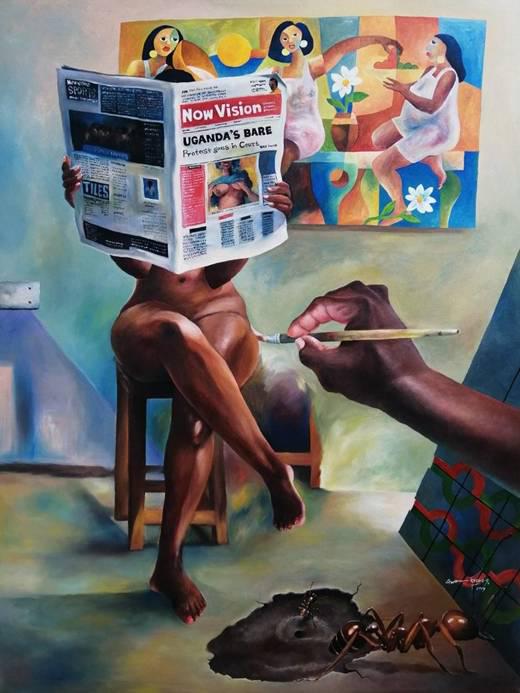

Soft Politics, Stephen Gwoktcho, 2019.

Two paintings from Stephen Gwoktcho, another lecturer from the art school at Makerere are in one corner of the gallery space. Unlike his counterpart Dr. Lillian Nabulime who maintains an active artist career outside the classroom, Gwoktcho rarely makes an appearance on the white wall and it can be felt in the work he showed here. His painting, Soft Politics falls short on concept ending up looking like one that could have been done by one of his students. Several ideas and concepts look to have been thrown in one artwork. The work also feels experimental, for an artist who has been placed in the master’s tier. A master artist should be one that has already discovered their voice and they seem to be following it consciously. Xenson calls it the artist’s DNA. His other work, Reflection tries to make up for the first one and breathes a little maturity with the focus on a singular concept and the colour play in the background but the coherence between the two works is lost. The two paintings might as well pass for work from two different artists. The color scheme and palette in Reflection reminds me of a better candidate who the curator should have chose in Gwoktcho’s place at this exhibition.

Joseph Ntensibe shouldn’t have missed at the show as his work is highly technical and seems to come from the same generation as the artists showing. Ntensibe is a master of color and light which he plays with in his paintings which are a cross breed between impressionism and realism.

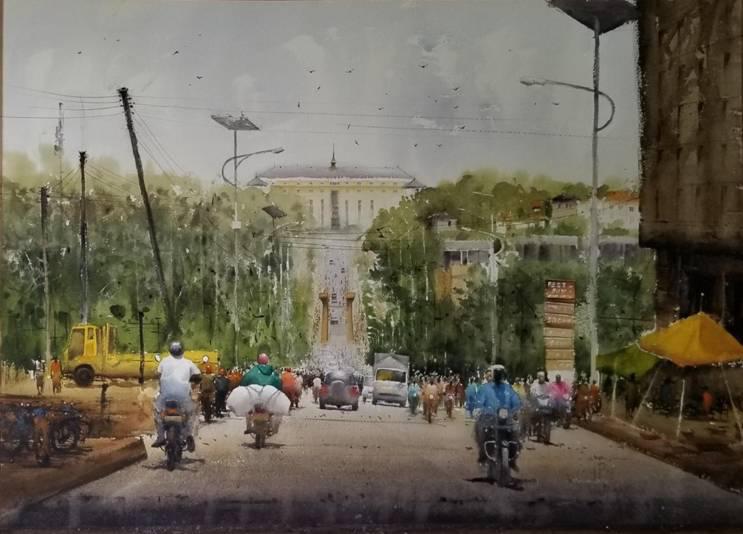

Royal Mile, Taga Nuwagaba, 2019.

Taga Nuwagaba’s water color paintings are also a spectacle to catch in this show. The six works mostly comprise of landscapes around Kampala, the capital. Of course Taga’s work lies heavily on the aesthetics side and it shows great skill in using what is the most difficult medium in traditional painting – water colour. Impressionistic in style, he weaves out the human figures, streets, vehicles and sky lines from hazy strokes of water colour. Taga is interested in documentation and he usually paints places that are under transformation and since Kampala is a young and fast growing city, his work is very much important. The first time I encountered Taga’s work was about 8 years ago when he had a show at International School of Uganda, I was in my late years of high school. The exhibition was called Totems and he painted each of the totems in Ugandan ethnic groups. Taga showed that the totems ideology is not only unique to the Baganda of central Uganda, but to all peoples in Uganda. This aspect demonstrates the similarity in African culture; regardless of geographical location.

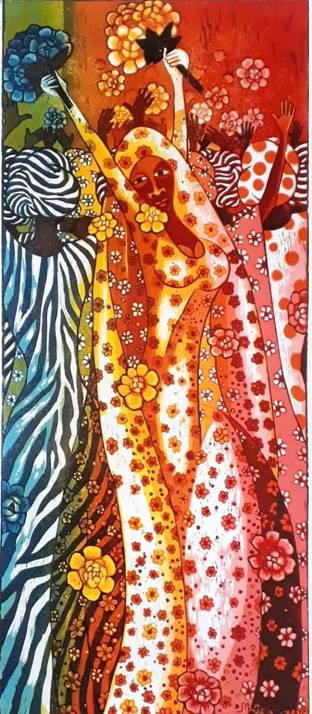

Omugole mu Bagole, Fred Mutebi, 2018

In another corner hangs the works of Fred Mutebi which are woodcut prints. Besides each print also hangs the matrix. Leopard patterns, zebra patterns, warm colors and abstract figures make up Mutebi’s print work which is stamped on the precious bark-cloth. No doubt, Mutebi has perfected the technique and medium of wood cut print as he does what is known as the “multi-color progressive reduction method”. The image is meticulously carved onto a wood plate, rolled with colored ink, and then registered onto a surface. The process is repeated five to six times on the same wood plate with different colors to complete the final image. At each stage, the colors transition from lightest to darkest. This particular technique of woodcut printmaking destroys the wood plate in the process. Carefully carved images and patterns are eventually removed in later stages to acquire the desired final print. The plate can never be used again.

Mutebi tells stories about the African environment, one of the works is titled Omugole Africa meaning ‘bride groom Africa’. It depicts a black woman lying down and it seems to speak of how the continent is this beautiful groom every ‘man” wants to walk down the aisle.

Simon Njami. Photo: David Damoison

What constitutes a master is the question that we should ask. For Simon Njami, the flame behind this fire, a master is an artist who has, apart from perfected their technique and medium but also one that has been endorsed by the big white boys, the western institutions. An artist who has shown at the international stage which includes platforms like Dak’Art or the Venice Biennale, reputable museums, international art fair or auction houses. For Pan-Africanism sake, a spirit that I heard from some of these senior artists, it could be a deliberate choice to avoid being in the hands of the west and therefore avoid being controlled and validated by the treacherous fellows. However, putting the politics aside, there is need for Ugandan artists to spread their wings. Maybe the older ones cannot catch up with the requirements of the contemporary art scene and globalizing a craft remains a job for the younger ones. The issue with most Ugandan artists who are comfortable with being recognized at home is that they end up producing work for the local market which is very small and less rewarding. Since the Ugandan eye is new to art, they are drawn to traditional techniques which means the artist should go back to the early 1900s or worse, the 1890s to resurrect Monet or Cezanne. This means that art promoters outside won’t be interested in ‘what has already been done’.

*

Most of the artists in this lot are locally consumed and no where on the international art scene. Apart from Sanaa Gateja, the rest wouldn’t be masters in the eyes of Simon Njami. Njami is right and there is a need for Ugandan practitioners to play at the big stage because there isn’t much the industry at home can offer. And also, is technique and aesthetics enough to bestow the title of master on one? What happens to the narrative, the stories around us, the pressing issues around us? Should the artists neglect the religious brainwash or Museveni’s dictatorship to celebrate the wildlife in Queen Elizabeth National Park? And why does a game park in Uganda still have a name of a British ruler? I like to believe that as artists, we have the capability and platform to tackle complex issues in our societies, let’s look beyond the surface. The surface in this case being techniques and mediums.