In the context of The Netherlands, where African American art has never had a dedicated solo show, I appreciate that the way the show was thought and how it is laid out responds to a rather didactic curatorial approach: the works are displayed in a loose chronological order, the wall-texts, although in Dutch, provide with a light contextual socio-political explanation of the time, they are accompanied by cultural artefacts that informed the visual arts and reinforced the mood of the time such as music, printed materials, and videos.

Raquel Villar-Pérez on TELL ME YOUR STORY, 100 years of storytelling African American art

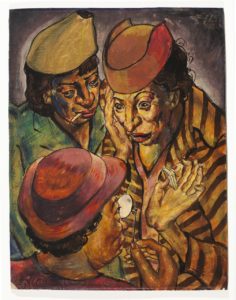

Charles White, The Bridge Party, 1938

Tell Me Your Story

100 years of Storytelling in African American art

With some 150 works and more than 45 artists, Tell Me Your Story, 100 years of Storytelling in African American art outstands as the first major show in the The Netherlands showcasing solely work by African American artists. The exhibition that opened to the general public on Saturday 8 February at Kunsthal KAdE in Amersfoort, can be visited until May 17.

Tell Me Your Story provides the visitor with an overview of Black visual arts of the past 100 years, that is from what is known as The Great Migration in the United States between 1916 and 1970 to date. Following a loose chronological order, the exhibition attempts to plot an evolution line that enables the viewer to appreciate and understand the origins and evolution of the African American visual arts, currently on vogue.

Dáreece Walker, Made in the USA, 2016. Charcoal on cardboard. Courtesy of the artist.

In the aftermath of the abolition of slavery in the United States, a large percentage of black population were living in the rural areas of the Southern United States. The poor economic situation and the prevalent racial segregation and discrimination of the South prompted some six million African Americans to leave in search of opportunities and better life conditions in the North and the West of the country, where the industry had revolutionised the economy. Numerous displaced people landed in Harlem, a neighbourhood in New York city, and according to the guest curator of the exhibition Rob Perrée “the breeding ground of everything that has happened in African American art over the past century.”

The exhibition borrows its title from the African tradition of storytelling, which helped black people preserve their customs through slavery; it examines how black artists have appropriated and re-created the art of telling stories visually ever since then. The 100 years timespan have been divided into five debatable periods that graciously fit into the five rooms of the Kunsthal KAdE: Harlem Renaissance, Post-Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights, Black Renaissance and Bloom Generation.

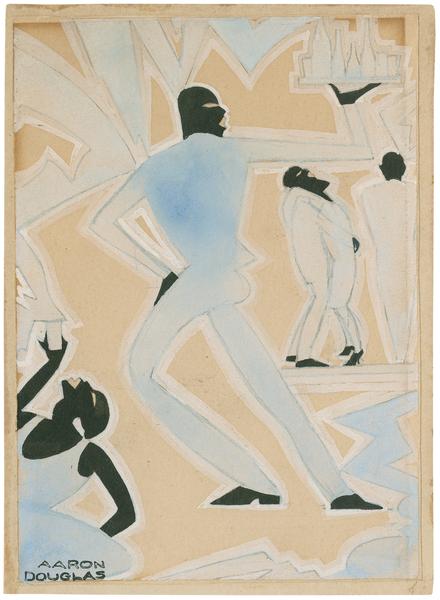

Aaron Douglas, Untitled (Night Club scene in blue and black), 1925. Gouache on paper mounted to paperboard. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY.

Embracing these five sections are three different visual aesthetics or strategies. The first one, which the curator frames between the release of Alain Locke’s seminal book The New Negro and the start of the Civil Rights movement, is characterised by the use of accessible at the same time than powerful figurative art. In line with the idea of representing the New Negro as described by the philosopher (1) and embodied by the poet Langston Hughes, artists such as Augusta Savage, Palmer Hayden, Hale Woodruff, Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Betye Saar, Romare Bearden, and Robert Colescott amongst others, endeavoured to portray not only the new lifestyle of black Americans but also their struggles of the time. A great deal of artists and intellectuals, such as the writer and activist James Baldwin, spent time in Paris to experience first-hand the insatiable wave of creativity that was flooding the French capital at the time of the European avant-gardes.

Romare Bearden, Carolina Sunrise, painting and collage. Walter O. Evans Foundation for Art and Literature, Savannah, GA.

These influences can be appreciated for instance in Aaron Douglas’ Untitled series of night club scenes, where the artist presents the new negro in a stylised manner that owes much to Cubism and Surrealism. Douglas represented him within night life scenery, a backdrop never used to portray black Americans before. The cubist influences in the work of Romare Bearden are even stronger, not without reason he has been described as the nation’s foremost collagist. Examined the daily life of his peers, both in the city and in the countryside; in Carolina Sunrise, we can appreciate an early morning family scene. The cut-out pieces retrieved from magazines, adverts or other artworks that Bearden borrows and resignifies, are part of complex compositions where solid bright colours are combined with transparencies and an odd game of back and fore. Betye Saar’s distinctive assemblages featuring repurposed materials such as washboards and jewellery boxes, portray the lives of generations of people who came before to address unresolved realities of the oppressed Black Americans.

Betye Saar, Sunny Land, mixed media. Collection Museum Hedendaagse Kunst de Domijnen, Sittard

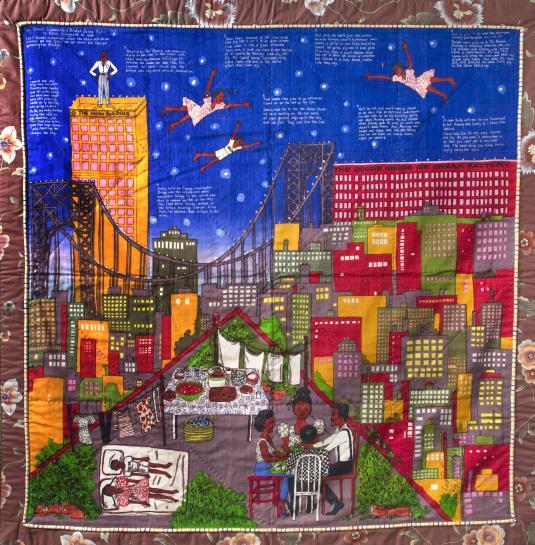

At the height of the Civil Rights struggle in the 1960s, African American artists deliberately blurred the boundaries between activism and art. Denounce is explicit. Text is widely included across the artworks becoming a direct way of telling stories. After having achieved success with her combative paintings and posters, Faith Ringgold turned to an art form with a long tradition amongst black communities, that of quilting. It enabled the artist to maintain her socio-political engagement through embroidered texts within the context of intricate pictorial compositions.

Faith Ringgold, Tar Beach #2, , 1990/1992, silkscreened quilt. Courtesy SCAD Museum of Art, Savannah, GA.

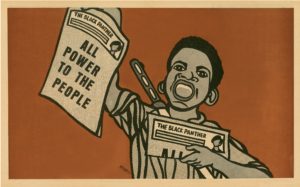

This is the time of the Black Power Movement, AfriCOBRA and the Black Panther Party. Emory Douglas was the Minister of Culture of the latter. Douglas’ converted art as a powerful weapon of mass propaganda. His work illustrated The Black Panther newspaper that had a peak circulation of 139,000 per week in 1970.

Emory Douglas, Paperboy, 1969. Courtesy of the artist.

The last of the three themes envisioned by Perrée comprises the diversification of stories. This is the decade of 1990s and 2000s, an era in which there is a substantial increase of an African American middle class, who not only accessed positions within the creative industries, but also started creating those of their own. They became advocates of the work of African American artists. According to the curator, three main reasons favoured the growing interest in African America arts: the collapse of the American art market in the late 1980s led to an interest in ‘cheaper’ Black artists, a rising appreciation of socio-politically engaged art, and the curiosity about ‘the other’. Consecrated artists such as Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, Kara Walker and younger generations represented by Kehinde Wiley, Paul Mpagi Sepuya or Jordan Casteel, find a fertile arena for producing their own stories and a ‘global’ art market that craves their narratives.

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Man reading newspaper), from Kitchen Table Series, 1990, pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The ambitious exhibition project is the epitome of the research undertaken by its guest curator, Rob Perreé, who has been studying Afro-American art for the past 30 years. In the context of The Netherlands, where African American art has never had a dedicated solo show, I appreciate that the way the show was thought and how it is laid out responds to a rather didactic curatorial approach: the works are displayed in a loose chronological order, the wall-texts, although in Dutch, provide with a light contextual socio-political explanation of the time, they are accompanied by cultural artefacts that informed the visual arts and reinforced the mood of the time such as music, printed materials, and videos.

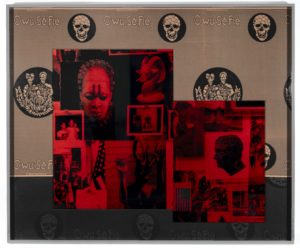

Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Darkroom Mirror (_2220049), 2018, archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, Inc, New York.

As a curious ever learning individual that lives in a context of perennial clash and redefinition of the ideas of nation and national subjectivity as it is the post-Brexit UK, with its own personal love-hate story with Black British arts and artists, I must confess that if on one hand I enjoyed the exhibition on the whole, the selection of artworks, the music, etc., on the other I missed the ribaldry of a more creative approach. Works such as Looking for Langston in which Isaac Julien revisits the life of Langston Hughes, Lotus by Sanford Biggers where the artist reopens the obscure history of slavery by portraying the bodies of slaves carried by a ship cargo container, and elevates their story by placing it within a lotus flower, symbol of enlightenment, or the work by the young artist Tschabalala Self whose work undertakes the venture of self-representation would have enabled the stories of the present enter into a nurturing dialogue with these of the past in the the same room.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Ombre à L’Ombre, 2019, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Maruani Mercier, Brussels.

-

The release of Alain Locke’s The New Negro awakened a new consciousness amongst black people and meant commence of what is known as the Harlem Renaissance: “A transformed and transforming psychology permeates the masses [ …] In this new group psychology we note the lapse of sentimental appeal, then the development of a more positive self-respect and self-reliance; the repudiation of social dependence, and then the gradual recovery from hyper-sensitiveness and “touchy” nerves, the repudiation of the double standard of judgement with its special philanthropic allowances and then the sturdier desire for objective and scientific appraisal; and finally the rise from social disillusionment to race pride, from the sense of social debt to the responsibilities of social contribution, and offsetting the necessary working and commonsense acceptance of restricted conditions, the belief in ultimate esteem and recognition.’ [Locke, 1925:10-11]