At different times throughout the Black community’s history – from the Black Lives Matter movement, Apartheid or police brutality – art in all its forms becomes the mouthpiece of opposition. Thus it is all the more profound that Kwanzaa was born during the Civil Rights movement when the Black community used its voice and artistic power to protest again discrimination.

Christabel Johanson on the history and art of Kwanzaa

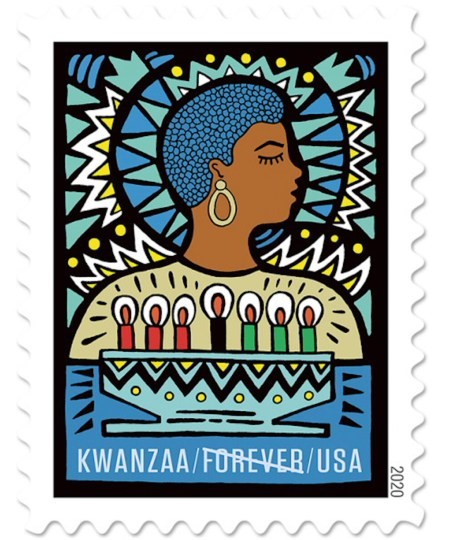

The Forever Stamp, Andrea Pippins, detail

The History and Art of Kwanzaa

As the festive season draws closer many people from the Afro-Caribbean community will be preparing to celebrate Kwanzaa. This global holiday, which is observed from 26th December until 1st January, holds both cultural and artistic importance for its revellers.

Kwanzaa was developed in 1966 during the Civil Rights movement by Dr Maulana Karenga. He created it as a way to honour family, community and culture. Popularised in America but also celebrated by the global African diaspora, Kwanzaa is not viewed as a religious festival. Instead Christians, Muslims, Jews and people from all walks of life are welcome to participate in Kwanzaa because it is a recognition of Afrocentrism and Blackness. Due to this openness to accept everyone, it is estimated that 18 million people now observe Kwanzaa.

In forming Kwanzaa, Dr. Karenga drew from African traditions to base the Seven Principles of Kwanzaa. Some of these principles include unity, purpose and creativity. Each principle is attributed to a day. For instance on day six, the word “Kuumba” is used. This comes from the Swahili word for “creativity”.

Dr. Karenga used Swahili as it is most commonly spoken across Africa. So it is a truly pan-African unifying language to express such principles. In fact the word “Kwanzaa” itself means “first fruits” because it coincides with the harvest period in the South of Africa.

Similar to the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, a candle is lit every day during Kwanzaa and families take time to discuss the corresponding principle of the day. Kuumba in particular asks everyone to make the community better and more beautiful. This has rooted Kwanzaa as a deeply artistic period of time which includes music, dancing, poetry, storytelling and art. Children are encouraged to paint and create things that express their interpretation of the holiday, family and their understanding of Kwanzaa.

In 2020 artist Andrea Pippins was commissioned to design a new Kwanzaa postal stamp named The Forever Stamp. It is described as having a blue-green palette and “Pippins centers a Black female in profile with a hoop earring, close-cropped hair, and a crown-like corona surrounding her head. A kinara (candle holder) holding red, black, and green candles completes the image.”

The Forever Stamp, Andrea Pippins (2020)

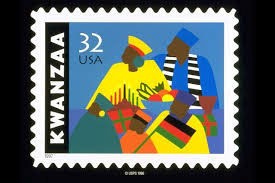

Pippins’ artwork is the latest in a line of eight Kwanzaa themed postal stamps. Synthia Saint James illustrated the first one in 1997, depicting an African family.

1st Kwanzaa Stamp, Synthia Saint James (1997)

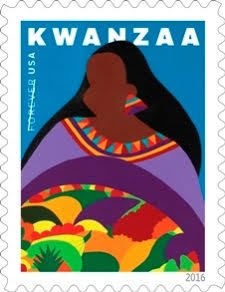

Then in 2016 she was asked to design her second stamp entitled Abundance. This time her stamp showed a woman of African descent holding a bowl of fruit and vegetables, signifying the time of harvest from which the word “Kwanzaa” is drawn from.

Abundance, Synthia Saint James (1997)

When asked about the inspiration for Abundance, Saint James previously revealed that “the emphasis of this stamp is abundance which symbolizes the first day, the first fruits. The stamp features a Black woman holding a large bowl filled with fruits, and vegetables; celebrating the first fall harvest and the abundance of both the spiritual and the material in our lives. I also created a painting called Abundance. In my painting, the fruits and vegetables, especially the grapes are overflowing in the bowl and you really get the feel of a bountiful harvest.”

Using art to give a progressive voice to the Black community is deeply ingrained in Kwanzaa. This ideology could be understood as Umoja (Unity) or Ujima (collective work and responsibility) within the Kwanzaa principles. Poetry here can be used to shine a powerful spotlight on social justice. For the Consideration of Poets by Haki R. Madhubuti has been named as one of these poems that many ponder over during Kwanzaa.

For the Consideration of Poets

where is the poetry of resistance,

the poetry of honorable defiance

unafraid of lies from career politicians and business men,

not respectful of journalist who write

official speak void of educated thought

without double search or sub surface questions

that war talk demands?

where is the poetry of doubt and suspicion

not in the service of the state, bishops and priests,

not in the service of beautiful people and late night promises,

not in the service of influence, incompetence and academic

clown talk?

Madhubuti urges us to remember the force of poetry (and art) to stand up against oppression and corruption. When we use our creative power, we not only create resistance against darkness but we create a beautiful form of peaceful protest in its wake. The poem was first published within Run Toward Fear in 2004. Madhubuti’s poem is not only a tool of resistance and defiance but also suggests the medium of poetry is a tool of resistance and defiance itself.

The final Kwanzaa principle explored will be Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics). What this principle encourages the community to do is to invest time and money back into itself. It is defined by Kwanzaa’s pioneers as a way to “build and maintain our own stores, shops, and other businesses and to profit from them together.” The Swahili meaning for “Ujamaa” literally translate into “extended family” or “brotherhood”. It reveals this principle sees the community as a large family with common interests, so that financial stability for the individuals bring financial stability for the whole. It seeks to recreate the family structure within smaller groups of non-related individuals, adding the economic support needed to sustain them.

The Tanzanian tribe of Makonde have an ancient tradition of carving which stems as far back as the 1700s. Makonde art is respected throughout Africa, and one piece in particular called Ujamaa has become a famous example of this sculpture style. This Tree of Life sculpture was made by Tanzanian artist Joesph Singombe and depicts the principle of Ujamaa.

Ujamaa, Joseph Singombe, Ebony Wood (mninga)

Singombe who was taught the craft by his father says “art runs in my blood, because my father was also an artist”. The sculpture is made from ebony wood, carved with a hand chisel and took four months to complete. The interlocking figures “represents the extended African family living and working together to achieve a common goal which is nurturing and caring for the family”. We can see that growth is based on the shoulders of those who came before and a solid structure allows the community to thrive and work towards a common goal. Today this might mean supporting Black-owned businesses, boycotting Capitalist stores that have a monopoly on the high street or working as an ally for the Black community. For white people who celebrate Kwanzaa, Umajaa may mean giving space to the Black community in areas that are traditionally dominated by white culture.

At different times throughout the Black community’s history – from the Black Lives Matter movement, Apartheid or police brutality – art in all its forms becomes the mouthpiece of opposition. Thus it is all the more profound that Kwanzaa was born during the Civil Rights movement when the Black community used its voice and artistic power to protest again discrimination. In fact Kwanzaa’s existence can be said to be a beautiful immersive piece of art itself. Kwanzaa is in opposition against the systematic oppression which seeks to dismantle Black communities. Kwanzaa is the celebration of Blackness and its culture. Kwanzaa is the embodiment of its principles and has inspired art work that does the same.