It is remarkable how snugly Rose’s work fits into a museum or gallery. In spite of the unsettling manner she attacks most of her topics- racism, white supremacy, female empowerment, occluded colored identity- they are frequently layered with a veneer of artistic respectability. They are also marked by a pliability that attracts considerable commercial possibilities.

Sanya Osha on the work of Tracey Rose

Installation View Shooting Down Babylon, Zeitz Mocaa, Cape Town, 2022

Tracey Rose: Thirty Years of Protest, Outrage and Alterity

Between February until the end of August 2022, the monumental Zeitz Mocca Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, hosted a retrospective of Tracey Rose’s work spanning thirty years. Rose, an exploratory multi-media artist, has expectedly gone through major phases covering outrage and repose amongst others. This broad spectrum of mind states and emotion attests to a restless creative temperament. Obviously, her ability to induce shock and outrage would tend to garner immediate attention and perhaps it would be worthwhile to dwell on this aspect of her work.

It is hopefully useful to situate Rose’s shock art between two kinds of contemporary artists who employ similar tactics, or preferably creative approaches. Two rebel artists: Daylyt, a California –based battle rapper who once attempted to defecate onstage in 2014 but was stopped and GG Allin, legendary US punk rocker who became a habitual onstage transgressor, smearing himself and his horrified audiences with excrement and gore. Allin, who died of a drug overdose in 1993, was an infamous legend of outrage and rebellion, an unrepentant and unsung prophet of unmitigated nihilism.

Installation View Shooting Down Babylon, Zeitz Mocaa, Cape Town, 2022

It is easy to be seduced by Rose’s predilection for revolt which often trumps the necessity for sufficient critique. Rose once attempted to defecate in full public view of her MA class at Goldsmith College, London during a performance of “Shittin’ Bullion” and understandably elicited a derisory reaction. Rose, it was claimed, “hated the UK.” There is a long history of anti-art movements and kinds of conceptual art that espouse formal and loose elements of rebellion. Yoko Ono’s cool and ironic anti-art statements readily come to mind.

Rose, in a famous performance piece, urinated on the wall that divided Israel and Palestine to generate mixed feelings of consternation and revulsion. Such elaborate acts of performativity that provoke strong responses and feelings from audiences are central to her practice. She’s understood to be concerned with questions of race, gender, sexuality and post(de)coloniality. These themes, underpinned with an unmistakable subalternity, veer squarely into Africanity. Here, more questions are raised about her motives as an artist. Her practice pits art versus anti-art coupled with rebellion, dissonance and repulsion. Initially, it isn’t clear if Rose is aware of the divergent responses she’s able to create in these conceptual tensions.

But perhaps her positionality as a colored South African subject is where we must look in order understand her various experiments in disjunctive art or an aesthetics of revolt. In South Africa, although he no longer resides in the country, Stephen Cohen’s equally provocative approach to performance perhaps bears one or two similarities with own Rose’s work. Cohen does not appear to have conflicted emotions about his identity and individuality. He seems to embrace his difference and distinctiveness wholeheartedly with a passion and concision that are fully defined and contained.

There is, on the other hand, at least at face value, a wild cat quality about Rose’s experiments. There is also a sense of rage that lashes out against confinement and strictures of the external gaze. The female body, more precisely, the black female body, by colonial fiat, is meant to be viewed, probed and consumed without restraint and consequence. Tropes of exoticization, otherization, rape and plunder have been the colonially ordained fate of the black body, both male and female.

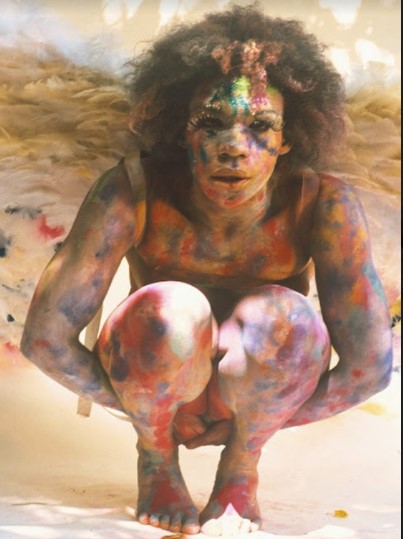

Ciao Bella, 2001 (video still)

The black female soul is where the entire world expects to unload its woes, worries and debaucheries. It is this kind of assumption that Rose rejects in its entirety. “I am no public bed or couch upon which you’d come to enact your fantasies of rape, plunder and unearned comfort” She is no anthropological cipher but, is instead, a knower/participant seeking her own language and a separate world for it.

It is necessary to consider the reality of the invisible South African colored (in South Africa, this means mixed race) woman. Perhaps the issue is rather more complex than that of mere visibility. It is probably more about subjugation and control. A controlled subject poses no threat, can be ignored, silenced and banished. Rose resists the tyranny of subjugation and control. But she does it in a declamatory fashion, flailing and bawling. It’s not only about a rejection of silence but also a boisterous celebration of angularity and alterity.

And so Rose would want us to believe she may be our worst nightmare. A hysterical wild cat who rambunctiously uproots all notions of social stability and good sense. Untamed, uncaged and unhindered. Indeed she could be your worst possible nightmare.

And then details of Rose’s life demarcate her limits. She holds down a job at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and is also a mother to a young son. Such important circumstances immediately spell the limits of what is possible as a rebel. The fact that she’s able to hold down a ‘normal’ job in spite of a stated anti-art, or at least, questioning intent, is remarkable and then add to that being a mother in a dehumanizing and perplexingly trans humanizing context plagued by super-exploitation, mass dispossession, child rape and serial murder. Obviously, you learn to wear different hats which lead to prevarication, equivocation and the all-too-familiar delineation of both existential and creative borders. You need to think about the consequences of being a breeder/parent, a loyal worker and ultimately, a defender of tradition.

Arguably, anti-art ostensibly leads down a road of anti-life which is always philosophically defensible. Anarchy, nihilism and rebellion all have cogent arguments in their favor. But there has got be a seedbed of conviction to back them up. There has got to be a concerted will to transcend any form of prescribed limits.

From the exhibition Shooting Down Babylon, Zeitz Mocaa, Cape Town, 2022

You can’t go to bed at night reeking of gore and feces because you’ve got to get the kids ready for school the next morning. And then society creeps right back in with its commands and expectations. You collapse into a heap of remorse, atonement and acceptance.

And this is how the meaning of Rose’s art needs to be framed: between the polarities of outrage and rebellion, on the one hand, and atonement and acceptance, on the other. It isn’t always an easy compromise, but it’s a reality she’s got to embrace because it is essentially her own truth. Two major works capture these vastly divergent polarities; her aforementioned filmed performance at a dividing territorial wall denouncing the Palestine/Israeli conflict and the supremely lyrical The kiss which depicts two naked lovers, a black man and white woman, possibly star-crossed, and locked in an insulated racial utopia of their own making.

Art Thou Not Fair, 2014 (detail)

Huge motifs include nudity and female sexuality and sensuality. Sometimes nudity stands to elicit quick and prompt attention. Other times, it is gauche and devoid of artifice, just simply the human body bearing the burden of its inexplicable power and vulnerability. And finally, sexuality is splayed like a pair of enticing thighs while the ultimate prize, the genitalia, is covered with perhaps, a fan. Indeed there are well-conceived transitions from artifice to gaucheness. A sly wink hints at fruits of a forbidden paradise.

It is remarkable how snugly Rose’s work fits into a museum or gallery. In spite of the unsettling manner she attacks most of her topics- racism, white supremacy, female empowerment, occluded colored identity- they are frequently layered with a veneer of artistic respectability. They are also marked by a pliability that attracts considerable commercial possibilities.

Thirty years of practice incorporating videos, film stills, photographs, drawings, prints and writings attest to a clearly questing creative animus. Rose’s art often careens between polarities of profanity and sublimity, beauty and repulsion, whimsy and gravity, bliss and rupture, simplicity and complexity.

A climactic revelation is that much of the initial anti-art tendencies of Rose’s work is indeed staunchly pro-art after all. Her rabble-rousing and rebellion can be comfortably subsumed into a conventional art canon due to deft packaging both by Rose and her team, on the one hand, and the magnificent Zeitz Mocca Museum which choreographed a tremendous show, on the other.

Some of the stand out works include, ‘Art thou not fair‘(2014) which foregrounds questions of race, the unaddressed reverberations of the slave trade and media stereotypes of black people.

From the exhibition Shooting Down Babylon, Zeitz Mocaa, Cape Town, 2022

‘Mandela’s Balls'(2013), a prettified installation series tackles South Africa evolving sociopolitical experiment.

In ‘Ciao Bella‘ (2001), Rose casts herself as Venus Baartman, a historic figure vilified, victimized and dehumanized on account of her natural physical attributes which racists found to be freakish. Here, Rose is exploring tropes of race and deracialization. As part of the series, there a reconfiguration of the biblical ‘Last Supper’ as well.

Indeed a critique of Rose’s work can be further extended by noting ingredients of sheen, gloss and artifice as integral parts of her present corpus. Imagine shielding a ring of fire with a golden frame. These polarities divulge widely creating an array of ambivalent views and emotions.

It is claimed that Jean Michel Basquiat and more especially, David Wojnarowicz didn’t readily fit the exiting templates for commercialization and canonization because of what was then considered to be their numerous creative oddities.

The shock element in art is now well accepted and perhaps somewhat passé. Arguably, Rose mixes shock, whimsy and visual acceptability with almost ridiculous ease. Her pet political topics, outrage and acceptable visual power meld in seemingly effortless symmetry. This says a lot about her knowledge of the intricacies of the art market and the politics of outrage. She would tend to be an artist who sits well within the home, art gallery and international circuit with considerable facility. This, undoubtedly, is rather unexpected.

In fairness, Rose isn’t merely a purveyor of shock and outrage. It seems motherhood and the demands of human nurturing have tempered her rage and delivered her to the more endearing shades of life. As such, she is capable of appreciating and exploring feelings of affect, more precisely, maternity, angular beauty and rare harmony. And so there is another level of contrast embedded in her work. It is a contrast that lends yet another layer of nuance and complexity to her practice. She’s shuttled through an impressive range of emotions and states of consciousness as a dynamically evolving artist. And she is apparently able to surprise us at every turn.