With washy and matte strokes, Muholi portrays herself in allusive physical forms, referencing both Zulu legends and gender disidentification imagery. Still, it is the striking presence, involving an unretractable gaze that infiltrates the viewers’ attention, and which is intrusively compelling.

Enos Nyamor on the paintings of Zanele Muholi

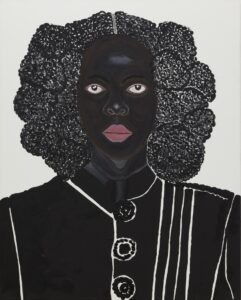

Zibuyile, 2021

Returning the Gaze

A Look at Zanele Muholi’s Latest Paintings

A personal lens: rays of actual, real life bent into high value colors imbue Zanele Muholi’s self-portraits, recently on view for the first time in New York City at Yancey Richardson. In “Awe Maaah!”, Zanele mirrors themselves, distorting the representation of their physical form—their body—in a recursive rendering of flat, outlined figures. The painter is the subject. In Zanele’s practice, the participant is the preferred title. Which means that to experience some of these paintings the audience must be prepared to consider an alternative language. With washy and matte strokes, Muholi portrays themselves in allusive physical forms, referencing both Zulu legends and gender disidentification imagery. Still, it is the striking presence, involving an unretractable gaze that infiltrates the viewers’ attention, and which is intrusively compelling.

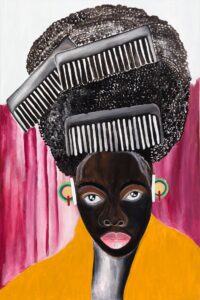

Phelela, 2021

By no means are these paintings unrealistic, and though they could manifest a variety of physical properties, they are also conflated from Muholi’s visual activism. No temporal exactness intrudes the paintings. In Phelela, 2021, an acrylic piece, the figure extends from the center of the canvas, with the head appearing as a smaller, blotched oval, under a layer of black, nappy Afro. The subject is embellished with a pair of earrings, and the combs seemingly float around the hair like a crown. Both the ball of hair and the oblong face form an inverted conical shape, which, when combined with the high value color, direct the viewer to the commanding gaze, which is especially emblematic of Muholi’s recent conceptual interrogation of queer lives in South Africa.

Itha, 2021

In “Somnyama Ngonyama,” an ongoing documentation of visual activism, consisting of Muholi’s photography, Zanele is both the photographer and the subject. With sharp contrast, the participant is invariably represented in majestic poses, elaborately silhouetted with a silky black. But the whiteness of the eyeballs flash through these dominantly black and white photographs. Sometimes gloomy, at other times resilient, but never jubilant. Every return to these photographs—some of which are on view alongside the new paintings—exudes changing sensibilities. Every view of these photographs, in their impervious emotional shield, induces a fresh spurt of confrontation; of emotional excavations; and of an inherent emotional opacity.

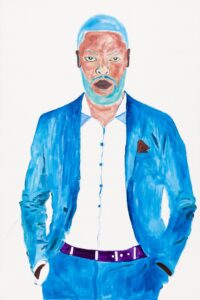

Phiwokakhe, 2021

But the paintings are themselves startling more than intrusive. Like the photographs they communicate raw existential vibrations. The unfettered desire for self-determination, which is also to mean to undertake acts of social deconditioning. No doubt the figures are filled in high value colors, which, nevertheless, are decisively matte, as they are composed of thin paint layers. For example, this resplendence is heightened in Phiwokakhe, 2021, a painting of a charmingly confident masculine figure in a blue suit, hands in a pocket, and integrated with the Muholi gaze. The sky blue of the hair, the slanted brows, and the beard nestle the dominating element—the Muholi gaze—concentrating liveliness on the face, filled in spirals of terracotta brown.

The fact of the paintings’ sizes exuding an immediate alertness is indisputable. With the increase in magnitude, the larger surface area stimulates an inflated awareness of the figures, and particularly of the recurring motif: the sultry eye contact. One gaze animates and is in flux. Another frozen and unflinching. The viewer’s eyes dances on the canvas, weighed down by experience, the figures’ eyes static and protruding a momentary exactness. Beyond this solid, Muholi-esque gaze’s symbolic function—as a reemerging element across Zanele’s oeuvre—it is also an act of discernment, of an immediate confrontation with the reality of staring into one’s reflection in a mirror. The surface excitement, hyphenated by the blotches of white on the colorful patterns on the canvas, also renders an atmosphere of untextured emotion, or a declaration of great uncertainty. There is shallowness in the placement of the figures in proximity to the background.

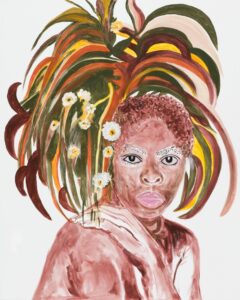

Phupho, 2021

Concerning the paintings’ texture and composition, there is much worth contemplating, and that is in order to respond to the restlessness that the works could induce. In this case, the sustained act of gazing ignites a contemplative resignation, but then it is the opacity enmeshing these figures that viewers are compelled to wrangle with. The relationship between this opacity, this particular brand of esoterism, and the images is distinct in Phupho, 2021, a tight frame of an androgynous figure, but, of course, with a set of the dominating “Muholi eyes.” It is the resignation in this piece, however, that enchants. The emotions are impermeable, even though the face glows with an acute satisfaction. But it is also a fecund expression that confer mysteriousness—with a poetic of opacity—and as such to be tolerated without facing subjugation.

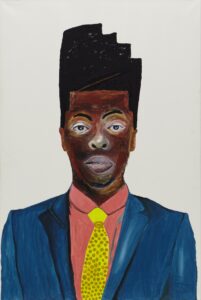

Tholakele, 2021

Precisely because the act of painting permits a flexibility in representation, it breaks the rigid wall erected by real life. The tone of a painting’s lighting can reflect a particular emotional aura that charges an object, and can be enhanced and made to appear wholesome and resplendent than real-life experience. In spite of their outward force, these figures thrust viewers into an uncertainty, and so while the gaze is solid, everything else is immaterial. In Tholakele, 2021, the viewers encounter the figure’s unwavering gaze. But the eyes emit a detached but impermeable, lush calmness. The feminine figure whose thick lips flourish in a pink that stands in steep contrast to the charcoal black of the skin texture and the shirt. Still, the gaze reifies the immateriality of the figure, and since the viewers are aware that those eyes belong to Muholi, then it becomes a question of whether limited, human bodily vessels are sufficient manifestation of identities. Which will mean that identity is more virtual than real.

Somile, 2021

Though a question lingers: are these paintings a fieldwork in narcissism? Another product of the temporal expanse of the 2020 pandemic, they press for an interrogation of what it means to be with oneself, to be oneself, and to live part of oneself conscious of all the contours in the body. Such is a task of immeasurable commitment. And although, across the seven paintings, the bodily outlines morph, the figures’ physical texture and the eyes are constant. They are all shades of black and brown, and which eliminates any fantastical structures that could imbue these paintings. Precisely because, even though there is a shift of figurative patterns, the brand of queerness that they all represent is innate to Blackness, and also to grappling with the reality of cultural heritage and both individual existence and identity. Each of the piece might permeate precise inspiration—on the series of events that led to the choice of particular mode of representation—but they also demonstrate an essentialist concern: are we, as humans, inherently bound to our race, that any act of disidentification, whether gender based or as a resistance to normativity, can never breach the totality of racial identity?